Chapter 3: Basic Emotion Theory and Social Constructivist Theory

Facial Expressions: Social Constructivist Perspective

Lisa Feldman Barrett and colleagues (Gendron, Roberson, van der Vyver, & Barrett, 2014b) noticed the limitations with Ekman’s methodology. She sought to replicate Ekman’s work by recruiting participants from the Himba tribe in Namibia. In her study, she used a methodology that differed from Ekman’s. She did not provide emotion labels to participants as Ekman did in his research. Instead, participants grouped similar facial expressions into six piles. In addition, she added a neutral/no emotion facial expression category. By making these changes, participants could no longer use process of elimination when completing the task.

Barrett found that Himba participants did sort similar emotions in the same groups. Specifically, both American and Himba participants placed smiles into one pile (joy!) and wide-eyes into a second pile (fear!), suggesting these two emotions are universal. Americans placed neutral and scowl (anger!) faces into two separate piles as well. But, Himba participants placed anger (scowl), disgust (grimace), and sad (frowns) expressions into the same pile! And Americans did not create separate piles for pouting (sad) or nose scrunches (disgust) either. These cross-cultural findings suggest that our culture teaches us the categories we use to group emotions and that different cultures have different categories. For the Himba, disgust, sadness, and anger belong in the same category; however, Americans view anger as a separate construct from disgust and sadness. Barrett and her team concluded that people are not born with emotions but learn emotions as they grow up. Because most of the emotions did not exhibit universality, she concluded emotions are not evolutionary adaptations.

For more information about Barrett’s work, please read the following article: About Face: Emotions and Facial Expressions May Not Be Related

Yale Expert Interview: Lisa Feldman Barrett.

Start at: 9:45; Stop at: 14:38

For Ekman’s response to Barrett’s claims, please read the following article.

Eastern and Western Differences in Facial Expression Interpretation

Other research shows that people raised in Western and Eastern cultures interpret facial expressions differently. Masuda, Ellsworth, Mesquita, Leu, Tanida, & van de Veerdonk (2008) recruited Japanese and American participants. Participants viewed cartoons in which sometimes the central figure’s facial expression matched the crowd and in other cartoons the central figure’s facial expression did not match the crowd. The emotions expressed in the cartoons included sadness, happiness, or anger. When viewing the cartoon, participants rated the degree of sadness, happiness, and anger felt by the central figure on a scale of 1 to 10.

Figures 5 and 6

Examples of Central Figure’s Emotions matched with sad (above) and happy (below) peripheral figures.

Figures 7 and 8

Examples of Central Figure’s Emotions mismatched with sad (above) and happy (below) peripheral figures.

From “Placing the face in context: Cultural differences in the perception of facial emotion,” by T. Masuda, P.C. Ellsworth, B. Mesquita, J. Leu, S. Tanida, and E. van de Veerdonk, 2008, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(3), p. 369 (https://doi.org/ 10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.36). Copyright 2008 by the American Psychological Association.

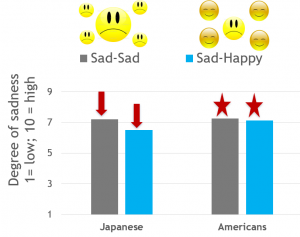

Figure 9 displays the findings for the dependent variable ratings of sadness. Japanese participants reported significantly higher levels of sadness when the central figure’s expression matched the crowd’s expression. But, when Japanese participants saw the central figure and crowd showed different emotions, they reduced the amount of sadness they perceived the central figure to express.

Figure 9

Japanese and American Participants’ Self-Reported Sadness

Adapted from “Placing the face in context: Cultural differences in the perception of facial emotion,” T. Masuda, P.C. Ellsworth, B. Mesquita, J. Leu, S. Tanida, S. and E. van de Veerdonk, 2008, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(3), p. 371. (https://doi.org/ 10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.36). Copyright 2008 by the American Psychological Association.

Now let’s look at American participants. American participants did not show differences in the amount of sadness they perceived the central figure to be expressing. For Americans, whether or not the central figure’s emotional expression matched the crowd did not influence their perception of the central figure’s emotion – Americans perceived the central figure was experiencing equal levels of sadness in both conditions. Researchers think we see these cultural differences in interpretation because Americans focus only on the central figure when interpreting emotions, whereas East Asians focus on the central figure AND the entire context.

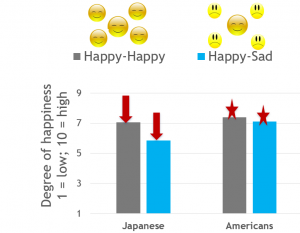

Figure 10

Japanese and American Participants’ Self-Reported Happiness

The findings for the dependent variable of happiness were the same as the findings for sadness (see Figure 10). The anger findings approached significance (p=.057).

Next, the researchers (Masuda et al., 2008) wanted to know WHY American and Japanese participants perceived the same facial expressions in different ways. So, they conducted a study using the same methodology, but this time used eye-tracking equipment to pinpoint where participants were looking.

Compared to Westerners, Japanese participants spent less time gazing at the central figure for angry, sad, and happy targets. Compared to Westerners, Japanese participants spent more time gazing at the background figures. It is important to note that although the researchers varied the race of the central and background figures, the results did not change.

Researchers also looked at where participants moved their gaze by seconds. At second 1, both Japanese and American participants focused their gaze on the central figure. By second 2, Japanese participants moved their gaze to the background figures, while American participants were still gazing at the central figure! So, when interpreting someone’s facial expression, both Japanese and American individuals immediately consider the individual feelings of the central figure, but Japanese quickly consider contextual cues as well.

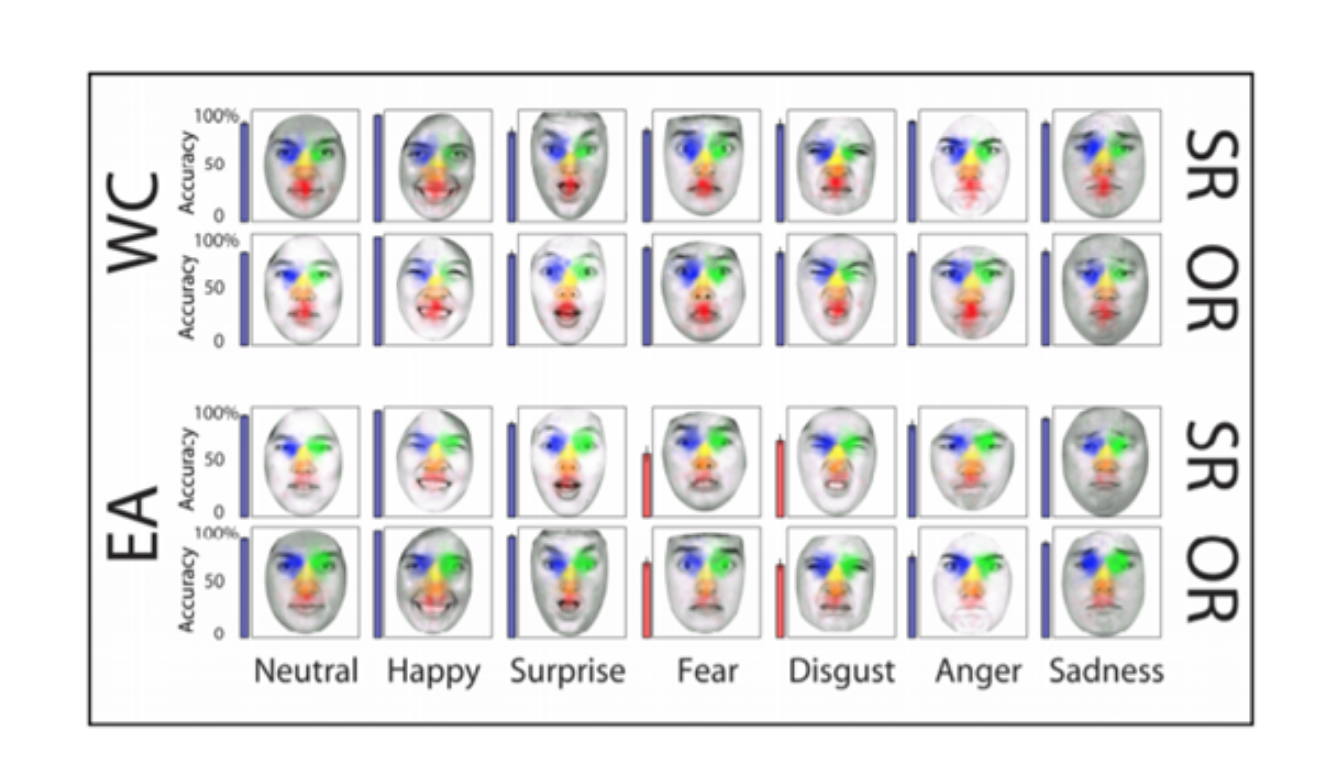

Another team of researchers (Jack, Blais, Scheepers, Schyns, & Caldara, 2009) conducted an eye-tracking study to investigate the parts of the face that Western and East Asian participants attend to when interpreting facial expressions. In this study, participants viewed 7 emotional expressions created based on Ekman’s FACS AU changes. While viewing each emotional expression, participants were asked to pick the emotion label from a list of the seven emotion words (similar to Ekman’s methodology).

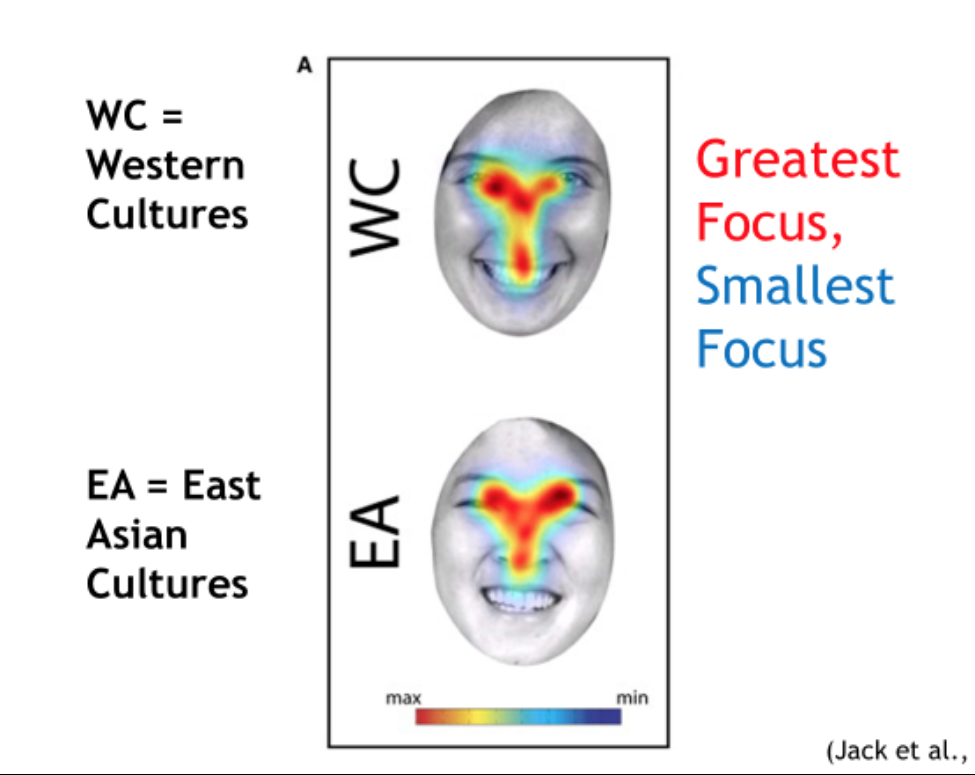

Similar to Masuda et al.’s (2008) findings, results did not differ by race. Figure 11displays the location where Western participants (top two rows) and East Asian participants (bottom 2 rows) were looking. Each column represents the seven emotions. The colors correspond to the part of the face the cultural groups were gazing at – lighter colors mean participants spent less time looking at that part of the face. Figure 12 shows eye patterns collapsed across the seven emotions – which makes it a bit easier to interpret the cultural differences.

East Asian participants focused significantly longer on the left and right eyes compared to the mouth. Westerners fixated on all parts of the face for an equal amount of time. Why are these findings important? Well, they identify another cultural difference in the way emotions are expressed and interpreted. East Asian individuals use people’s eyes to identify their emotion, while Westerners use all parts of the face. So, it is highly possible that East Asian and Westerners could look at the same face and conclude the individual is experiencing two different emotions! In fact, American participants correctly identified the seven emotions, whereas East Asians confused fear with surprise and disgust with anger. Emotions researchers have also suggested that East Asians may not look at the mouth because people raised in East Asian cultures are less likely to move their mouths during an emotional experience. Of course, it’s hard to know the causal direction.

Figure 11

Eye-Tracking Results Across Seven Emotions for Western Culture (WC) And East Asian Culture (EA) Participants

Note. WC = Western Culture; EA = East Asian Culture; SR = Same Race; OR = Other Race.

From “Cultural Confusions Show That Facial Expressions Are Not Universal,” by R.E. Jack, C. Blais, C. Scheepers, P.G. Schyns, and R. Caldara, 2009, Current Biology, 19, Online Supplemental Material (Cultural Confusions Show that Facial Expressions Are Not Universal) (Cultural Confusions Show that Facial Expressions Are Not Universal). Copyright 2009 by Elsevier Ltd.

Figure 12

Eye-Tracking Results Collapsed Across Seven Emotions for Western Culture (WC) And East Asian Culture (EA) Participants

From “Cultural Confusions Show That Facial Expressions Are Not Universal,” by R.E. Jack, C. Blais, C. Scheepers, P.G. Schyns, and R. Caldara, 2009, Current Biology, 19, p. 1544 (Cultural Confusions Show that Facial Expressions Are Not Universal). Copyright 2009 by Elsevier Ltd.