Chapter 11: Negative Self-Conscious Emotions

Single-Emotion Theory

According to Single-Emotion Theory, the only required cognitive appraisal for shame/embarrassment is evaluation of the self. Evaluation of the self occurs when we feel that other people’s attention is focused on us. Subjective feelings during this state include feeling exposed, flustered, and confused. But, unpleasantness is not a required appraisal – so people may feel negative or positive during this event. Moral or social conventional violations are not required eliciting events. Sabini and Silver point out that people feel shame/embarrassment regarding personal characteristics such as being physically unattractive, feeling stupid, or incompetent – none of which are violations.

Single-Emotion Theory (Sabini & Silver, 1997) define two types of self – the core self and the presented self. The core self represents the entire global self, whereas the presented self represents the parts of the self that other people observe. The presented and core selves may or may not match.

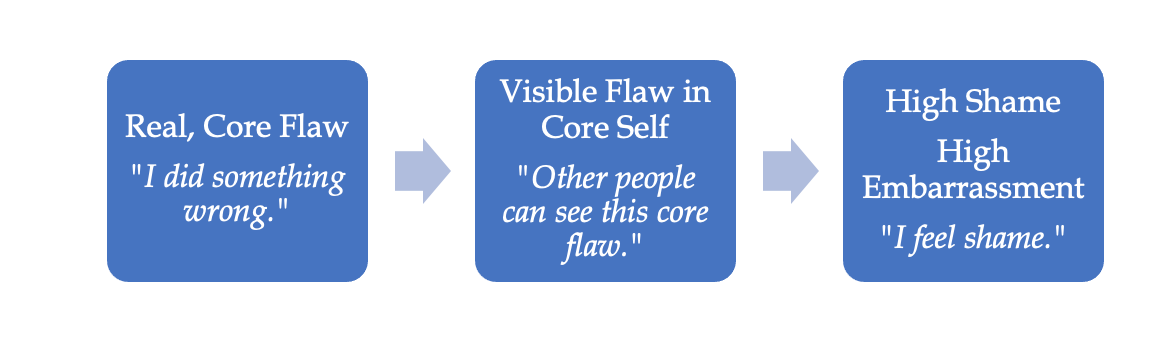

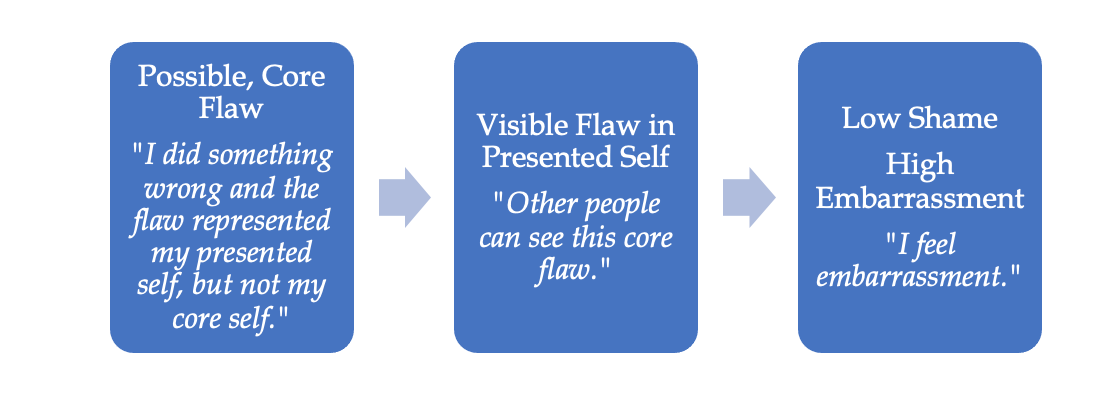

Single-Emotion Theory (Sabini & Silver, 1997) define two types of flaws. The real visible flaw occurs when we THINK that a real flaw in our core self was shown to other people. In this instance, the present self would match the core self. The possible (apparent) visible flaw occurs when we THINK that other people have evidence to conclude a flaw in our core self, but this flaw may or may not have occurred?. With the perception of a possible flaw, two options may occurs. First, the possible, visible flaw might occur when we know that we did not commit a flaw in the core self, but we are aware that other people might conclude we did reveal a flaw in the core self. The other option could be that we did commit a flaw in the core self, but we do not think other people saw this flaw. In the possible flaw, the presented self does not match the core self.

Let’s talk about how these flaws and selves relate to shame and embarrassment. According to Single-Emotion Theory, shame is caused by a flaw in one’s core self occurs. For shame, we must perceive that a real flaw in our self/character is visible to other people. Thus, when we feel shame, we perceive that a real flaw of our broad character or self has been revealed to others. Embarrassment is caused by a flaw in one’s presented self. Embarrassment occurs when we perceive that other people POSSIBLY see a flaw in our core self. With embarrassment, people definitely see the flaw in the presented self, but we are not sure whether people attribute this flaw to our core self. With embarrassment, we as the actors, know that this possible flaw does not represent our core self. But, we think that other people have REASONABLE BASIS or enough evidence to conclude we revealed a core flaw.

Remember, shame and embarrassment are different words that represent different intensities of the same emotion. Our cognitive appraisals determine whether we label the emotion as shame or embarrassment. After we experience the emotion, when we describe our experience, we use the real versus possible cognitive appraisal to place a label on the emotion.

If we believe a flaw visible in the presented self that people may or may not see as a flaw in the core self → EMBARRASSMENT

This theory is based on our thoughts about our own transgression and our interpretations of whether other people can see a possible transgression. So, this theory comes from a cognitive appraisal perspective.

To determine whether you feel shame or embarrassment, you want to think about how you interpret the type of flaw.

If you perceive that you did something wrong and you think other people can see it – this is a real, visible flaw. Any other flaws are apparent/possible.

If someone perceives that they committed a flaw in the real core self, and this flaw was revealed to other people, then they would report high levels of shame and high levels of embarrassment. This represents the high intensity form of the shame/embarrassment emotion. People would label this emotion shame.

If someone perceives that they committed a flaw in the presented self, but this flaw does not reveal a flaw in their core self, then they would report low levels of shame and high levels of embarrassment. This represents the low intensity form of the shame/embarrassment emotion. People would label this emotion embarrassment.

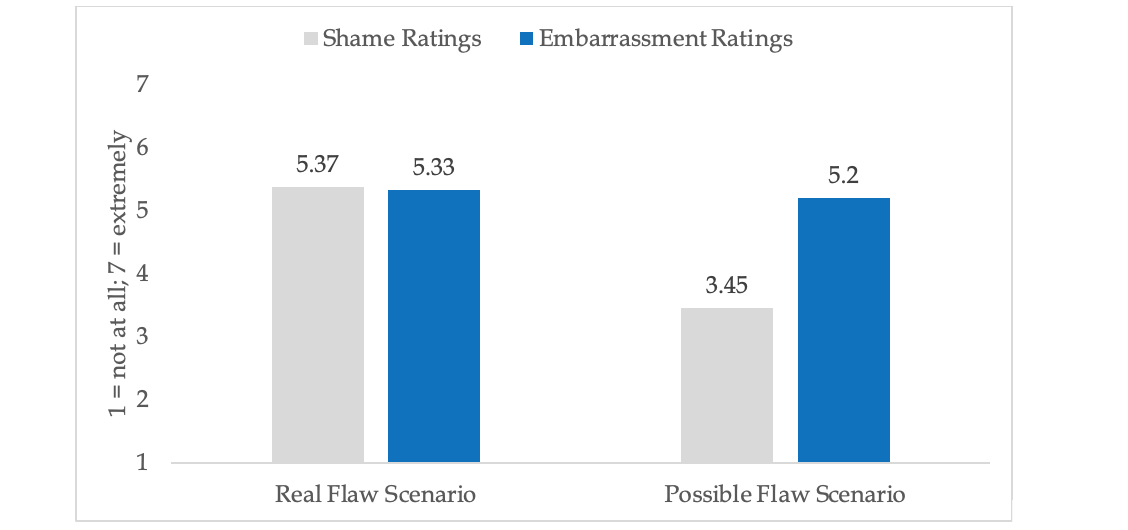

Let’s review a study (Sabini et al., 2001) that tested whether Distinct Emotions Theory or Single-Emotion Theory was correct. In this study, participants were given 20 scenarios and asked to imagine themselves in each scenario and then to self-report their emotions. The independent variable was whether the scenarios included a real flaw or a possible flaw. The dependent variable was the feelings participants reported after reading each scenario. These feelings were shame, embarrassment, fear, guilt, anger, and regret.

Real Flaw → High Levels of Self-reported Shame only!

Possible Flaw →High Levels of Self-reported Embarrassment only!

Real Flaw → High Levels of Self-reported Shame and Embarrassment!

Possible Flaw → High Levels of Self-reported Embarrassment, but Low Levels of Self-reported Shame!

Flaw in Core Self

Presented Self = Core Self

Flaw in Presented Self

Presented Self Does not Equal Core Self

Figure 16

Self-reported shame and embarrassment for real flaw and possible flaw scenarios (Sabini et al., 2001)

Now, let’s discuss evidence for Single-Emotion Theory’s view of guilt and anger. In this study (Sabini et al., 2001), all the scenarios participants read now have possible flaw scenarios. The independent variable is whether the scenario includes one of the following: 1) reasonable basis, 2) no reasonable basis, or 3) guilty of offense. The guilty condition was included as a comparison to the other two conditions in which the person did not actually commit an offense.

Table 12

Description of independent variable conditions and predictions (Sabini et al., 2001)

| Independent Variable Condition | Description of Scenario | Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Reasonable Basis | Audience has enough evidence (“good reason”) to believe you revealed a flaw, but you did not reveal a flaw. | High Embarrassment |

| No Reasonable Basis | audience perceives you have a flaw, but they do NOT have a good reason or enough evidence to make this conclusion | High Anger |

| Guilty | You are guilty of an offense and someone exaggerates your violation. | N/A |

Anger was significantly higher in the no reasonable basis condition than the other two conditions. This relates to the unfairness appraisal we discussed with anger. We would likely perceive it unfair that someone concluded we committed a flaw when there was zero evidence! In the no basis scenario, shame and embarrassment were lower than in the other two conditions. This suggests that only when we perceive other people have a good reason for concluding we committed a flaw, then we label that emotion shame/embarrassment. People could draw this reasonable conclusion because we actually committed the flaw (as in the guilty scenario) or because they have good evidence, even though we did not do it (as in the reasonable basis condition). The guilty with exaggeration condition shows that when we commit an offense and other people know about our offense, we experience high levels of shame and embarrassment, and low levels of anger.

For an overview of Single-Emotion Theory (Sabini & Silver, 1997), please see Table 13. In general, this theory suggests that shame and embarrassment are different intensities of the same emotion. Shame occurs when other people’s perceptions of the real, serious flaw is correct, causing us to experience this high arousal, negative emotion. Embarrassment is when we think other people saw a flaw in the core self, but it was a flaw in the presented self, causing this low arousal, negative emotion.

Table 13

Overview of Single-Emotion Theory view of shame, embarrassment, and guilt

| Emotion | Overview |

|---|---|

| Shame | We perceive a real, serious flaw of the self is revealed |

| Embarrassment | When we communicate that although there seems to have been a real core flaw of the self, there actually was not. |

| Anger | When we think people’s perception of a possible core flaw is unreasonable. |