Chapter 12: Pride – A Positive Self-Conscious Emotion

Cognitive Appraisals

Condition 1: Stable attribution (due to IQ, personality)

Condition 2: Unstable attribution (due to effort, situation)

Condition 1: Specific Attribution – one domain in life / good act

Condition 2: Global Attribution – whole self

2 Dependent Variables:

DV #1: Self-reported authentic pride

DV #2: Self-reported hubristic pride

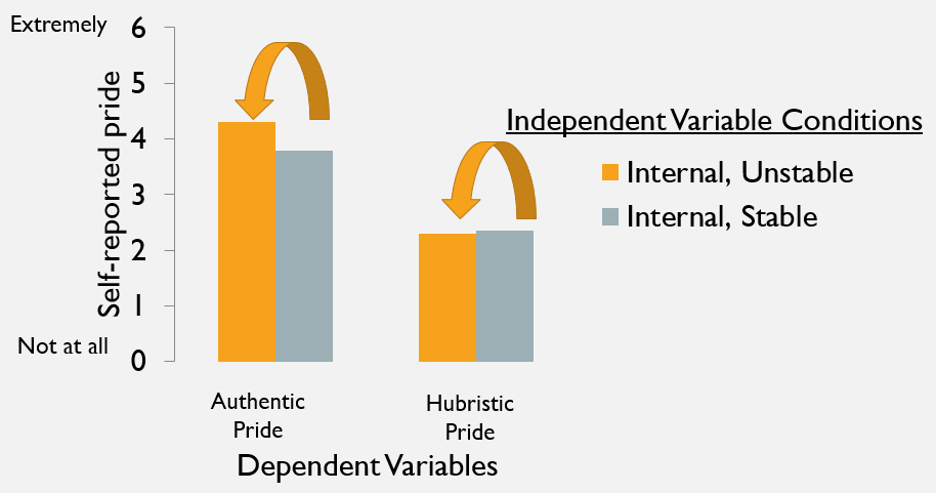

Figure 9

Findings for IV #1 Stability Attributions

Long Description

The image is a bar graph depicting self-reported pride levels under different conditions. The graph has two main bars representing dependent variables: Authentic Pride and Hubristic Pride. Each bar contains two segments, orange and gray, representing independent variable conditions. The orange segment signifies “Internal, Unstable,” while the gray segment signifies “Internal, Stable.” Both bars are topped with an arched arrow illustrating a relationship or comparison between the two segments. The vertical axis is labeled “Self-reported pride,” scaled from 0 (Not at all) to 6 (Extremely).

Adapted from “The psychological structure of pride: A tale of two facets,” by J.L. Tracy and R.W. Robins, 2007c, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), p. 518. (https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.506) Copyright 2007 by the American Psychological Association

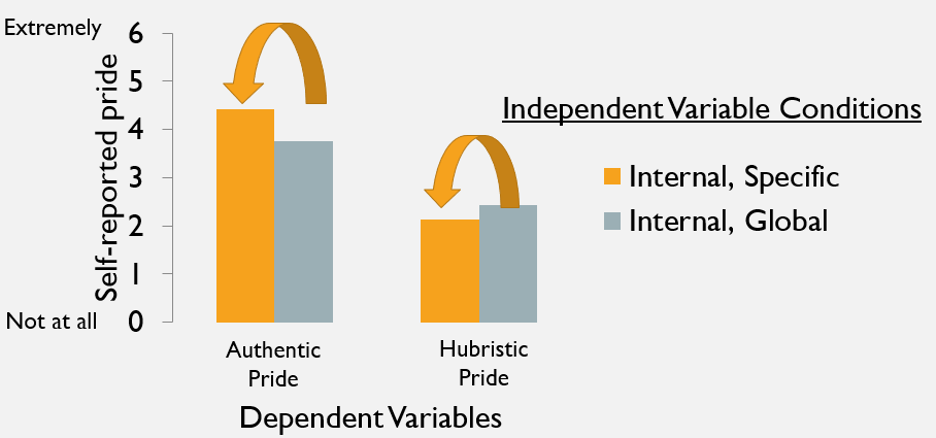

Figure 10

Findings for IV #1: Stability Attributions

Long Description

The image is a bar graph comparing self-reported pride levels under two independent variable conditions, labeled as “Internal, Specific” and “Internal, Global.” Two sets of bars are presented, representing the dependent variables: “Authentic Pride” on the left and “Hubristic Pride” on the right. Each set includes one orange bar and one gray bar.

The y-axis is labeled “Self-reported pride,” with a scale ranging from 0 (“Not at all”) to 6 (“Extremely”). The x-axis indicates “Dependent Variables.” In the “Authentic Pride” category, the orange bar (Internal, Specific) is taller than the gray bar (Internal, Global). In the “Hubristic Pride” category, the gray bar (Internal, Global) exceeds the height of the orange bar (Internal, Specific). An arrow above each bar pair visually indicates which bar is higher.

A legend in the top right corner denotes the color coding: orange for “Internal, Specific” and gray for “Internal, Global.”

Adapted from “The psychological structure of pride: A tale of two facets,” J.L. Tracy and R.W. Robins, 2007c, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), p. 518. (https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.506) Copyright 2007 by the American Psychological Association

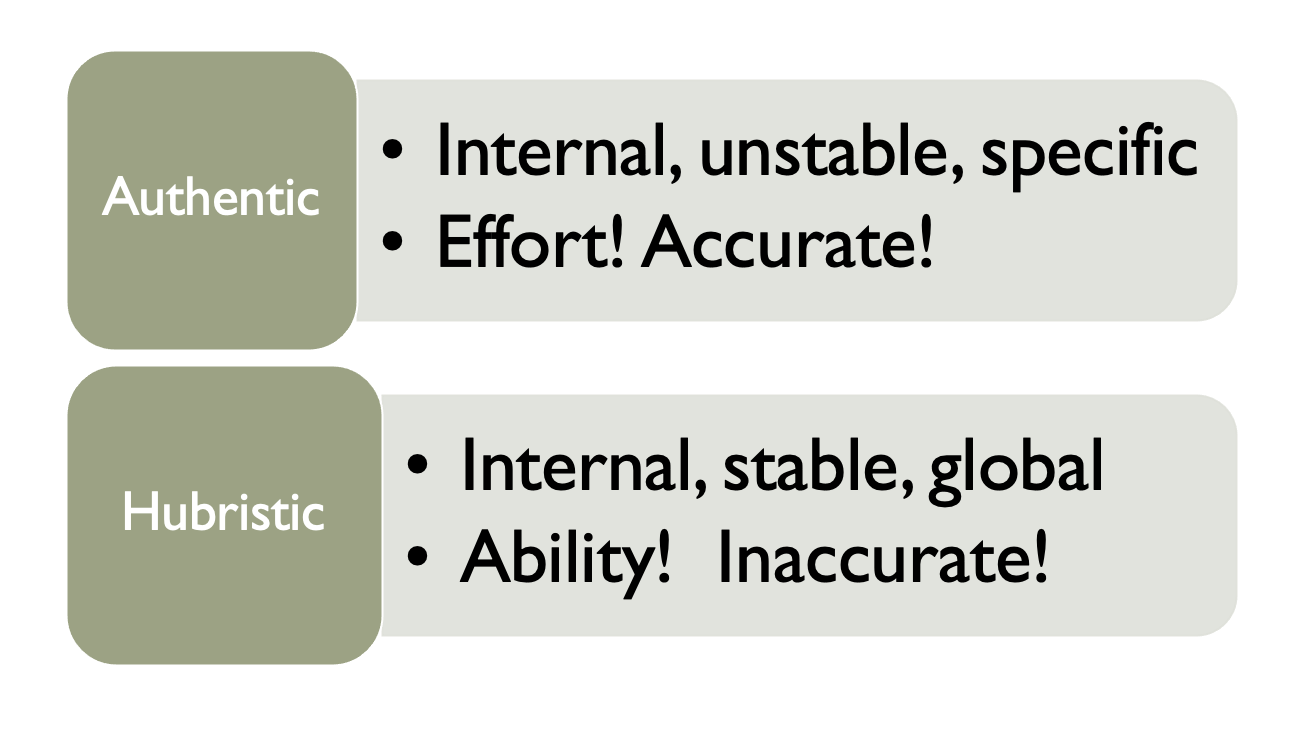

Long Description

The image consists of two rectangular sections with rounded green squares on the left side. Each section contains descriptive text. The top section has the word “Authentic” inside the green square, leading to a gray area with bullet points, listing “Internal, unstable, specific” and “Effort! Accurate!”. The bottom section has the word “Hubristic” inside the green square, connected to a gray area with bullet points stating “Internal, stable, global” and “Ability! Inaccurate!”.

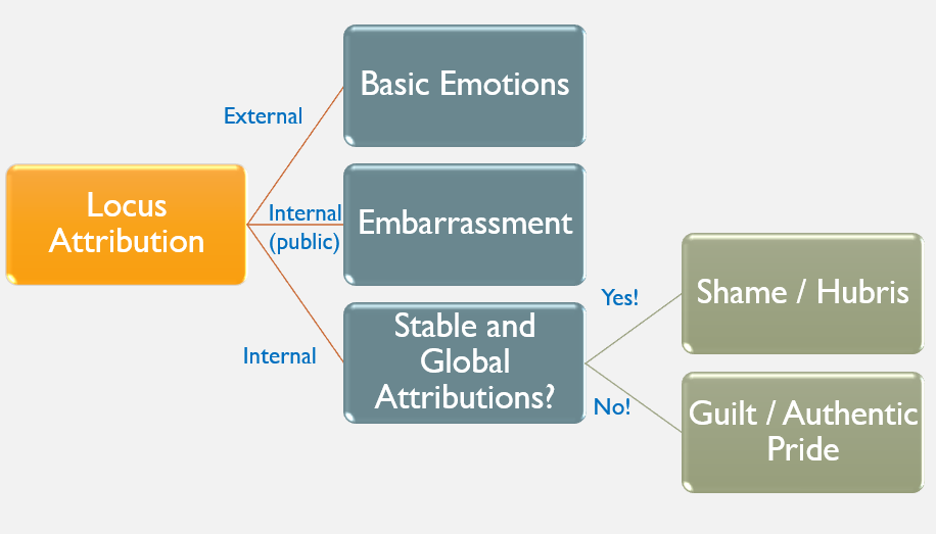

Process Model of Self-Conscious Emotions

Figure 11

Process Model of Self-Conscious Emotions (Tracy & Robins, 2004a)

Long Description

The image displays a decision tree diagram illustrating types of emotions based on locus attribution. On the left, an orange rectangle labeled “Locus Attribution” branches into three lines: “External,” “Internal (public),” and “Internal.” The first line leads to a blue-gray rectangle labeled “Basic Emotions.” The second line points to another blue-gray rectangle labeled “Embarrassment.” The third line connects to a blue-gray rectangle labeled “Stable and Global Attributions?” which has two branches: “Yes!” leading to a green rectangle labeled “Shame / Hubris,” and “No!” leading to another green rectangle labeled “Guilt / Authentic Pride.”

Adapted from “Putting the self into self-conscious emotions: A theoretical model,” J.L. Tracy and R.W. Robins, 2004a, Psychological Inquiry, 15(2), p. 110 (Psychological Inquiry, 15(2), p. 110) Copyright 2004 by Lawrence Erlbaum

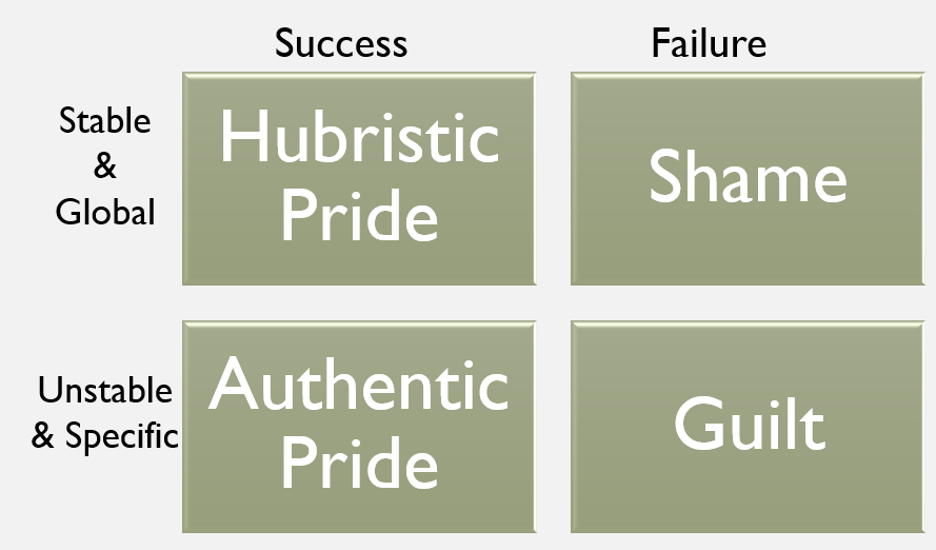

Figure 12

Three Attributions for Self-Conscious Emotions

Long Description

The image is a matrix grid with two rows and two columns, displaying a categorization of emotions based on stability and specificity of causes (vertical axis) and success versus failure (horizontal axis). The vertical axis on the left is labeled “Stable & Global” for the top row and “Unstable & Specific” for the bottom row. The horizontal axis at the top is labeled “Success” for the left column and “Failure” for the right column. Each quadrant contains a term: “Hubristic Pride” in the top-left, “Shame” in the top-right, “Authentic Pride” in the bottom-left, and “Guilt” in the bottom-right. Each quadrant is shaded in a muted green color with white text.

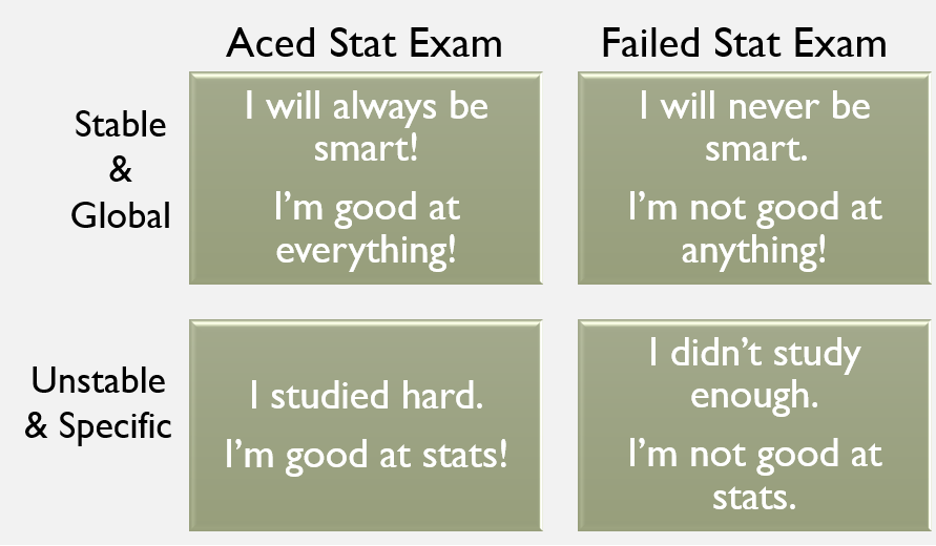

Figure 13

Examples of each Cognitive Attribution

Long Description

The image is a grid with four sections, comparing reactions to acing or failing a statistics exam. It is divided into two columns labeled “Aced Stat Exam” and “Failed Stat Exam.” Each column is paired with rows labeled “Stable & Global” and “Unstable & Specific.” The background of each section is a light olive green with white text.

Transcribed Text:

Aced Stat Exam Stable & Global I will always be smart! I’m good at everything!

Failed Stat Exam Stable & Global I will never be smart. I’m not good at anything!

Aced Stat Exam Unstable & Specific I studied hard. I’m good at stats!

Failed Stat Exam Unstable & Specific I didn’t study enough. I’m not good at stats.