Chapter 11: Negative Self-Conscious Emotions

Facial Expressions

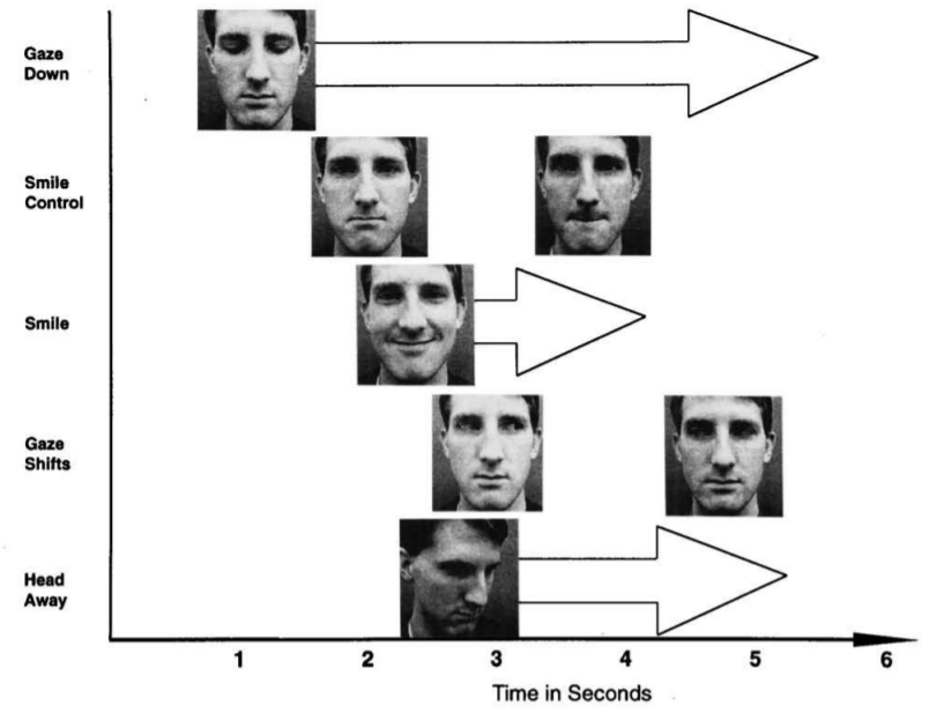

In Keltner’s (1995) classic study, he utilized data from participants who had recently completed the Directed Facial Action (DFA) task in an earlier unrelated study. This task is described here . The data from participants who reported feeling embarrassment or amusement during the DFA was analyzed. Specifically, Keltner analyzed the facial expressions and bodily changes of participants in the 15-second rest period following each display of an emotional expression. Compared to participants who felt amused, embarrassed participants…

- looked down faster, spent a longer period of time looking down, and frequently changed their gaze location.

- showed more “smile controls” or attempts to conceal a smile or the zygomatic AU change.

- more lip presses (AU 24)

- turning head away from camera and more downward head movements

- more face touches

Figure 1 shows the facial changes that occurred overtime during the embarrassment experience. The duration of each facial change is from the left edge of the photograph to the end of the arrow. Thus, downward gaze is the facial change that last the longest, followed by head away. It is interesting to note that the embarrassment facial expression comprises several facial changes over a period of six seconds.

Figure 1

Facial Expression Change Over Time and Average Length of Each Change (Keltner, 1995)

Long Description

The image is a time-based graph illustrating the progression of facial expressions. The x-axis is labeled “Time in Seconds” and spans from 1 to 6 seconds. The y-axis lists five facial expression categories from top to bottom:

- Gaze Down

- Smile Control

- Smile

- Gaze Shifts

- Head Away

Each row corresponds to one expression and contains a sequence of facial images taken at different time points. Arrows between the images indicate the direction and timing of expression changes.

- Gaze Down is shown from seconds 1 to 5.

- Smile Control appears between seconds 2 and 4.

- Smile occurs around second 3.

- Gaze Shifts is noted around second 2.

- Head Away is observed from seconds 2 to 5.

Reproduced from D. Keltner, 1995, Signs of appeasement: Evidence for the distinct displays of embarrassment, amusement, and shame. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(3),p. 445 (https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.441) Copyright 1995 by the American Psychological Association.

Some theorists believe the embarrassment facial expression serves an adaptive purpose – to show appeasement to others (Keltner, 1995; Castelfranchi & Poggi, 1990). The appeasement hypothesis states that when an individual violates a social norm, this elicits anger in group members. By displaying the embarrassment facial expression after violating a norm, people acknowledge that they are aware of their violation and exhibit submission to maintain the social order. Yet, Keltner acknowledged the DFA task is one unique situation that elicited embarrassment and that some of the touching displays could be due to the physiological attachments and not really to embarrassment.

In a follow-up study Keltner (1995) had participants watch a videotape and free list the emotion expressed by the individual in the tape. Participants rated the individuals showing embarrassment as sad, followed by nervous. Participants did not specifically state the term embarrassment (this relates to the Widen and Russell (2011) study below).

In another study, Keltner (1995) explored whether shame and embarrassment facial expressions were unique. In this study, participants watched video recordings of 12– to 13-year-old Caucasian and African American males completing an IQ test. Clips of the IQ test showing facial expressions of amusement, enjoyment, anger, disgust, and shame and guilt were identified using Ekman and Friesen’s (1978) FACS. After watching each clip, participants selected an emotion term (amusement, enjoyment, anger, disgust, and shame and guilt) that described the males’ facial expressions.

Findings showed that participants selected embarrassed labels for the embarrassed expressions displayed by the adolescent males and picked the shame label for males expressing shame. Interestingly, participants were more accurate in labeling embarrassment and shame when they were evaluating expressions of African-American boys compared to Caucasian boys.

Figure 2

Proportion of Sample Selecting Emotion Label of Embarrassed and Shameful Adolescent Males

Shameful Adolescent Male: Shame; African American – 82, Shame; Caucasian – 52, Disgust; African American – 5, Disgust; Caucasian – 20.

Long Description

The image is a bar graph titled “Proportion of Sample Selecting Emotion Label of Embarrassed and Shameful Adolescent Males.” It compares how different adolescent male groups, categorized as African American and Caucasian, select emotion labels for embarrassment and shamefulness. The graph features two sets of bars for each emotion: one for “Embarrassed Adolescent Male” and another for “Shameful Adolescent Male.” The y-axis represents the proportion of the sample selecting each emotion label, ranging from 0 to 100.

The “Embarrassed Adolescent Male” category has two bars: a blue bar for African American males and an orange bar for Caucasian males. The blue bar reaches approximately 68% for embarrassment, while the orange bar reaches approximately 53%. For the label “Shame,” the African American males show a low proportion, while the Caucasian males reach approximately 10%.

The “Shameful Adolescent Male” category also includes two bars. The blue bar for African American males extends to approximately 82% for “Shame,” while the orange bar reaches 52%. For “Disgust,” the African American males have a low proportion, while the Caucasian males reach about 20%.

Adapted from D. Keltner, 1995, Signs of appeasement: Evidence for the distinct displays of embarrassment, amusement, and shame. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(3),p. 452 (https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.441) Copyright 1995 by the American Psychological Association.

In Keltner and Buswell (1996; the classic study we discussed above), they sought to identify the facial expressions associated with embarrassment, shame, and guilt. Participants were shown 14 facial expressions for five seconds. For each of the 14 emotional expressions, they viewed 2 photos of the same female poser and 2 photos of the same male poser. After viewing each photo, they were presented with a list of 14 emotion labels and instructed to select the emotion that was the best match for previously viewed facial expression. They had to select the emotion label within 10 seconds. The 14 emotion labels were:

- Amusement

- Anger

- Awe

- (self)-contempt

- Disgust

- Embarrassment

- Fear

- Guilt

- Happiness

- Pain

- Sadness

- Shame

- Surprise

- Sympathy

- No Emotion

Below, are the photos that the researchers believed corresponded to embarrassment, shame, and sadness.

Table

Keltner and Buswell’s (1996) Facial Expressions of Embarrassment, Shame, and Sadness

Adapted from D. Keltner and D.T. Cordaro, 2017, Understanding multimodal emotional expressions: Recent advances in basic emotion theory. The science of facial expression, p. 59-61. Copyright 2017 by Oxford University.

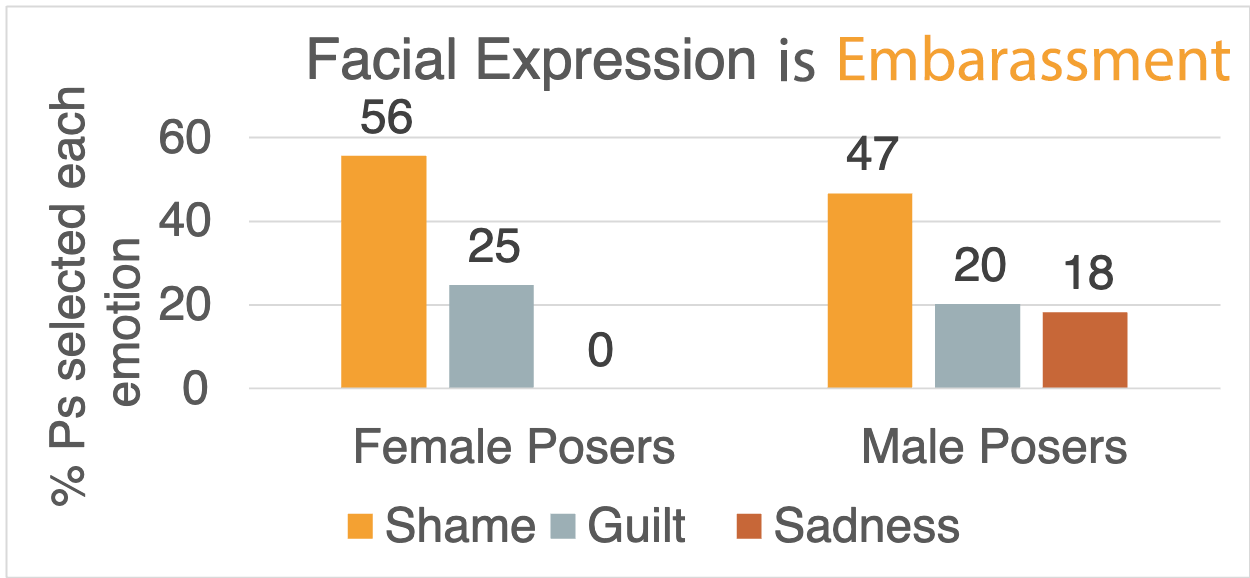

Figure 4 shows the percentage of participants who selected each emotion when the facial expression displayed was embarrassment. For both female and male posers, a majority of participants selected embarrassment (51% when viewing female posers; 56% when viewing male posers). Not shown in the figure, only 7% of the sample judged the embarrassment photos to be shame.

Figure 4

Percentage of participants who selected each emotion for embarrassment expression

Male Posers: Shame – 47, Guilt – 20, Sadness – 18

Long Description

The image consists of a bar chart on the left side and a photograph of a person on the right side. The chart is titled “Facial Expression is Embarrassment,” displaying the percentage of participants who selected each emotion (Shame, Guilt, Sadness) for female and male posers. The y-axis is labeled “% Ps selected each emotion,” ranging from 0 to 60. For female posers, the orange bar representing “Shame” is at 56, the blue bar for “Guilt” is at 25, and there is no bar for “Sadness.” For male posers, the orange bar for “Shame” is at 47, the blue bar for “Guilt” is at 20, and the brown bar for “Sadness” is at 18. The right side of the image shows a photograph of a person with dark braided hair, wearing a black top, slightly smiling with their hand resting on their chin.

Note. Researchers considered 7.2% as above chance; So, when less than 7.2% of sample selected label, label not included in data. Adapted from D., Keltner, & B.N. Buswell, 1996, Evidence for the distinctness of embarrassment, shame, and guilt: A study of recalled antecedents and facial expressions of emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 10(2), p. 166, (https://doi.org/10.1080/026999396380312). Copyright 1996 Psychology Press. Photo reproduced from D. Keltner and D.T. Cordaro, 2017, Understanding multimodal emotional expressions: Recent advances in basic emotion theory. The science of facial expression, p. 59-61. Copyright 2017 by Oxford University.

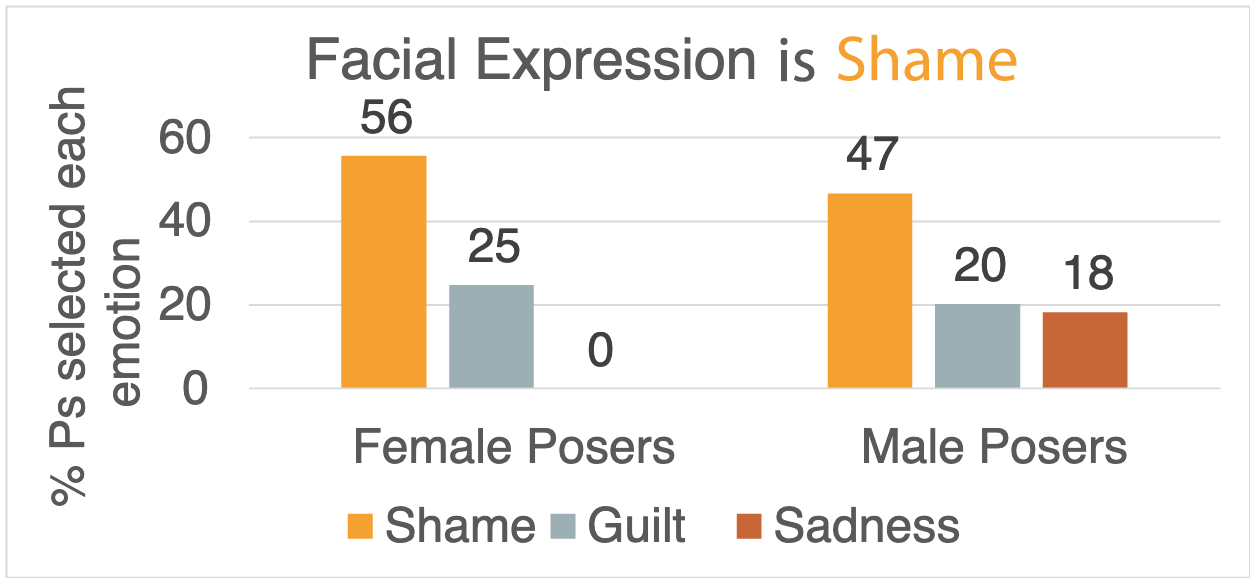

Figure 5

Percentage of participants who selected each emotion for shame expression

Male Posers: Shame – 47, Guilt – 20, Sadness – 18.

Long Description

The image is divided into two parts: a bar graph on the left and a photograph of a woman on the right. The bar graph illustrates the percentage of participants who selected each emotion (shame, guilt, and sadness) for shame expression among male and female posers. The y-axis represents the percentage selected, ranging from 0 to 60%. For female posers, 56% selected shame (orange), 25% selected guilt (light blue), and 0% selected sadness (brown). For male posers, 47% selected shame, 20% selected guilt, and 18% selected sadness. Above the graph is the title “Facial Expression is Shame.” On the right, there is an image of a woman with her eyes closed, wearing a black top, viewed from the shoulders up. The overall tone is analytical and informative.

Table 4

Percentage of participants who selected each emotion for basic emotions expression (Keltner & Buswell, 1996

| “Basic” Emotion | Female Posers | Male Posers |

|---|---|---|

| Anger | Anger: 66.7

Disgust: 17.2 Contempt: 11.1 |

Anger: 87.3

Contempt: 07.7 |

| Contempt | Disgust: 66.5

Contempt: 17.5 |

Disgust: 45.6

Contempt: 32.5 |

| Disgust | Disgust: 88.9 | Disgust: 85.9 |

| Fear | Fear: 83.2 | Fear: 91.9 |

| Happiness | Happiness: 89.7 | Happiness: 74.8 |

| Sadness | Sadness: 84.0 | Amusement: 15.6

Sadness: 78.6 |

| Surprise | Surprise: 72.2

Fear: 12.5 Awe: 11.8 |

Surprise: 84.4

Awe: 12.2 |

Note. Researchers considered 7.2% as above chance; So, when less than 7.2% of sample selected label, label not included in data. Adapted from D., Keltner, & B.N. Buswell, 1996, Evidence for the distinctness of embarrassment, shame, and guilt: A study of recalled antecedents and facial expressions of emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 10(2), p. 166, (https://doi.org/10.1080/026999396380312). Copyright 1996 Psychology Press.

Figure 6

Keltner and Buswell’s Facial Expressions Related to Guilt

Adapted from D. Keltner and D.T. Cordaro, 2017, Understanding multimodal emotional expressions: Recent advances in basic emotion theory. The science of facial expression, p. 59-61. Copyright 2017 by Oxford University.

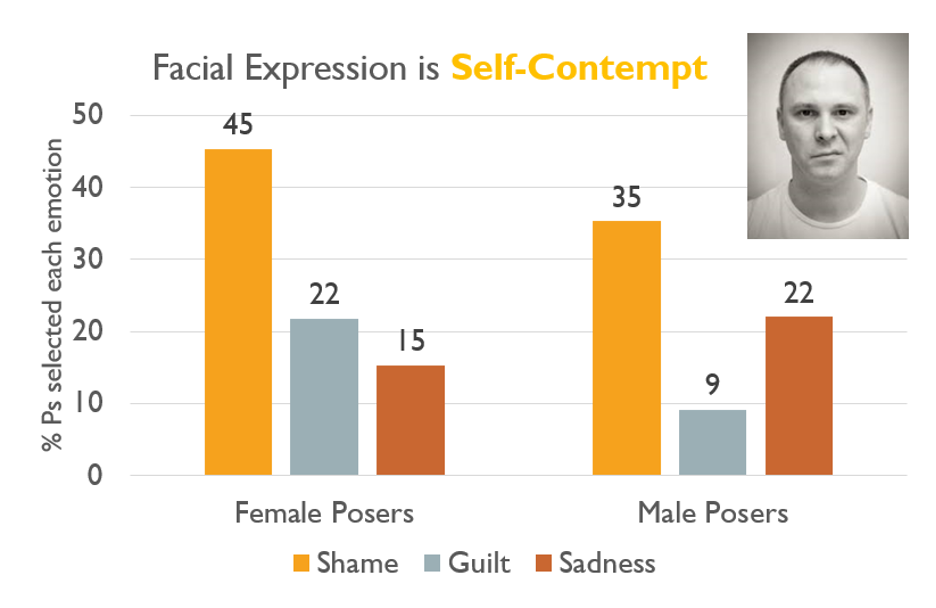

As can be seen in Figure 7, most participants reported self-contempt facial expressions to be shame.

Figure 7

Percentage of participants who selected each emotion for self-contempt expression

Male Posers: Shame – 35, Guilt – 9, Sadness – 22.

Long Description

The image features a bar chart comparing the percentage of selected emotions for “Female Posers” and “Male Posers” based on a facial expression identified as self-contempt. The title above the chart reads “Facial Expression is Self-Contempt.” The vertical axis represents percentages ranging from 0 to 50.

For “Female Posers,” the chart shows three bars: an orange bar labeled “Shame” at 45%, a gray bar labeled “Guilt” at 22%, and a brown bar labeled “Sadness” at 15%. For “Male Posers,” there is an orange bar for “Shame” at 35%, a gray bar for “Guilt” at 9%, and a brown bar for “Sadness” at 22%.

In the top right is a grayscale portrait of a bald man with a neutral expression, presumably used to illustrate the facial expression being analyzed.

Note. Researchers considered 7.2% as above chance; So, when less than 7.2% of sample selected label, label not included in data. Adapted from D., Keltner, & B.N. Buswell, 1996, Evidence for the distinctness of embarrassment, shame, and guilt: A study of recalled antecedents and facial expressions of emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 10(2), p. 166, (https://doi.org/10.1080/026999396380312). Copyright 1996 Psychology Press. Photo reproduced from D. Keltner and D.T. Cordaro, 2017, Understanding multimodal emotional expressions: Recent advances in basic emotion theory. The science of facial expression, p. 59-61. Copyright 2017 by Oxford University.

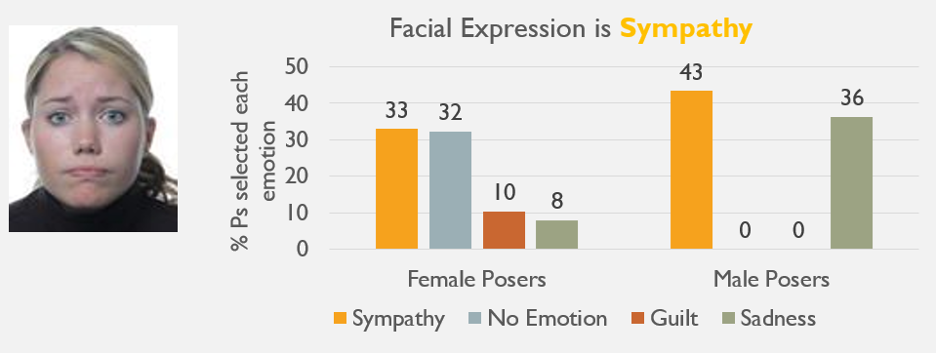

For the sympathy facial expression (Figure 8), the findings differed according to the gender of the poser. For female posers, 1/3 participants labeled the expression sympathy and another 1/3 selected no emotion. For male posers, 43% selected sympathy, while 36% selected sadness. Guilt was not selected at beyond chance levels.

Figure 8

Percentage of participants who selected each emotion for sympathy expression

Male Posers: Sympathy – 43, No Emotion – 0, Guilt – 0, Sadness – 36.

Long Description

The image is a combination of a photograph and a bar chart. On the left, there is a portrait of a person with light-colored hair styled back, displaying a facial expression that might be interpreted as neutral or slightly concerned. They are wearing a dark turtleneck. On the right, a bar chart is displayed under the title “Facial Expression is Sympathy,” highlighted in yellow. The y-axis represents the percentage of participants (% Ps) who selected each emotion, ranging from 0 to 50.

The x-axis categorizes the data into “Female Posers” and “Male Posers.” For female posers, the chart shows bars for Sympathy (33%), No Emotion (32%), Guilt (10%), and Sadness (8%). For male posers, there are bars for Sympathy (43%) and Sadness (36%), with no percentages for Guilt or No Emotion. The color scheme assigns orange to Sympathy, gray to No Emotion, brown to Guilt, and green to Sadness.

Note. Researchers considered 7.2% as above chance; So, when less than 7.2% of sample selected label, label not included in data. Adapted from D., Keltner, & B.N. Buswell, 1996, Evidence for the distinctness of embarrassment, shame, and guilt: A study of recalled antecedents and facial expressions of emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 10(2), p. 166, (https://doi.org/10.1080/026999396380312). Copyright 1996 Psychology Press. Photo reproduced from D. Keltner and D.T. Cordaro, 2017, Understanding multimodal emotional expressions: Recent advances in basic emotion theory. The science of facial expression, p. 59-61. Copyright 2017 by Oxford University.

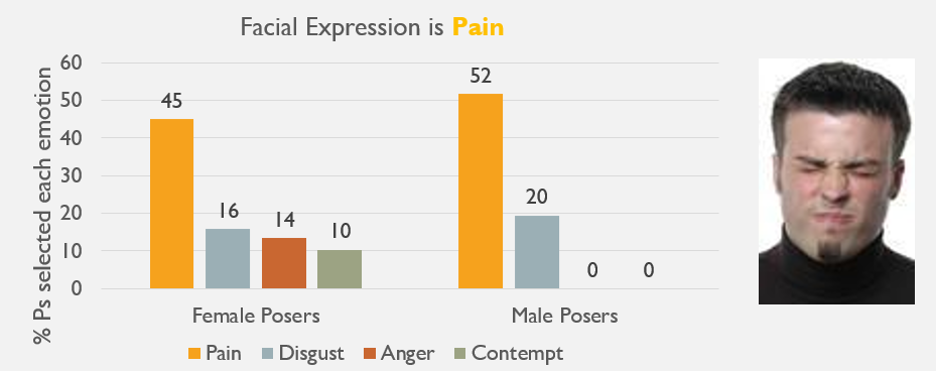

Figure 9

Percentage of participants who selected each emotion for pain expression

Male Posers: Pain – 52, Disgust – 20, Anger – 0, Contempt – 0.

Long Description

The image displays a bar chart alongside a photograph of a person. The chart is titled “Facial Expression is Pain,” with two categories: “Female Posers” and “Male Posers.” The y-axis represents the percentage of participants who selected each emotion, marked in increments from 0 to 60. Four emotions are represented by differently colored bars: orange for Pain, blue for Disgust, red for Anger, and green for Contempt. In “Female Posers,” 45% identified the expression as Pain, 16% as Disgust, 14% as Anger, and 10% as Contempt. For “Male Posers,” 52% identified Pain, 20% Disgust, and 0% for both Anger and Contempt. To the right, a photograph shows an individual with closed eyes and a tense facial expression, suggestive of pain.

Note. Researchers considered 7.2% as above chance; So, when less than 7.2% of sample selected label, label not included in data. Adapted from D., Keltner, & B.N. Buswell, 1996, Evidence for the distinctness of embarrassment, shame, and guilt: A study of recalled antecedents and facial expressions of emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 10(2), p. 166, (https://doi.org/10.1080/026999396380312). Copyright 1996 Psychology Press. Photo reproduced from D. Keltner and D.T. Cordaro, 2017, Understanding multimodal emotional expressions: Recent advances in basic emotion theory. The science of facial expression, p. 59-61. Copyright 2017 by Oxford University.

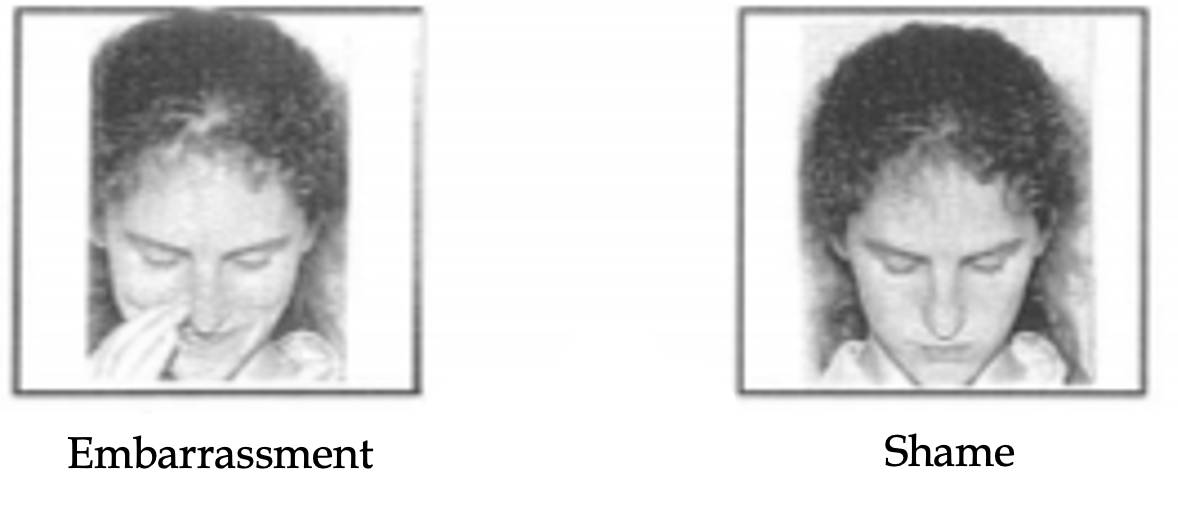

Figure 10

Facial Expression Photos from Haidt and Keltner (1999)

Long Description

The image consists of two side-by-side black and white photographs of a person displaying different facial expressions. On the left, the expression is labeled “Embarrassment,” showing the person’s head slightly turned, eyes closed, and a hand partially covering the face, suggesting a smile. On the right, the expression is labeled “Shame,” with the person’s head tilted down, eyes closed, and a neutral or slightly tense mouth. Both images are framed in simple rectangular borders and have white backgrounds.

Adapted from J. Haidt and D. Keltner, 1999, Culture and facial expression: Open-ended methods find more expressions and a gradient of recognition. Cognition & Emotion, 13(3), p. 234 (https://doi.org/10.1080/026999399379267) Copyright 1999 Psychology Press.

Figure 11 shows that for the shame and embarrassment facial expressions, participants got more correct when they completed the forced choice method versus the free label method. It is important to note that recognition rates when free labelling the original six basic emotions ranged from . 41 (for disgust) to .94 (for happiness).

Figure 11

Proportion of Correct Forced Choice and Free Labelled Responses for Shame and Embarrassment Facial Expressions

Embarrassment; Forced Choice – 0.48, Embarassment; Free Labelling – 0.31

Long Description

The image is a bar chart illustrating the proportion of correct identifications of facial expressions in photos labeled as “Shame” and “Embarrassment” under two conditions: “Forced Choice” and “Free Labelling”. The vertical axis represents the proportion correct, ranging from 0.00 to 1.00. The horizontal axis indicates the facial expression categories: “Shame” and “Embarrassment”. Each category has two bars; the blue bar represents the “Forced Choice” condition, and the orange bar represents the “Free Labelling” condition. For “Shame”, the “Forced Choice” bar is taller with a value of 0.66, while the “Free Labelling” bar is shorter, at 0.32. For “Embarrassment”, the “Forced Choice” bar is also taller, at 0.48, compared to the “Free Labelling” bar at 0.31. A legend is present at the top, indicating the color coding for the two conditions.

Adapted from S.C. Widen, A.M. Christy, K. Hewett, and J.A. Russell, 2011, Do proposed facial expressions of contempt, shame, embarrassment, and compassion communicate the predicted emotion?. Cognition & Emotion, 25(5), p. 901. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2010.508270 Copyright 2010 Psychology Press.

Figure 12

Proportion in of Participants Responses for Shame and Guilt Expressions in Free Labeling Session

Embarrassment; Correct – 0.31, Embarrassment; Happy – 0.24, Embarrassment; Sad – 0.23, Embarrassment; Cognition – 0.01

Long Description

The image is a bar chart with two grouped bars, each representing different facial expressions in photos: “Shame” and “Embarrassment.” The y-axis is labeled “Proportion Participants’ Responses,” with values ranging from 0.00 to 1.00. Each bar is stacked and color-coded to indicate four categories: Blue (Correct), Orange (Happy), Gray (Sad), and Yellow (Cognition).

For “Shame”: the bar shows 32% Correct (blue), 42% Sad (gray), and 5% Cognition (yellow), with zero for Happy (orange). For “Embarrassment”: the bar shows 31% Correct (blue), 24% Happy (orange), 23% Sad (gray), and 1% Cognition (yellow). A legend at the top specifies the colors corresponding to each category.

Note. Cognition category includes free labeled responses of “confused, curious, debating, doubtful, perplexed, skeptical, suspicious, uncertain, and unsure” (Widen et al., 2011, p. 900). Adapted from S.C. Widen, A.M. Christy, K. Hewett, and J.A. Russell, 2011, Do proposed facial expressions of contempt, shame, embarrassment, and compassion communicate the predicted emotion?. Cognition & Emotion, 25(5), p.903. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2010.508270 Copyright 2010 Psychology Press.