Chapter 8: Fear, Anxiety, and Stress

Fear Facial Expressions: Basic or Social Constructivist?

Facial expressions change during a fear experience. Keep in mind that the fear facial expression might differ based on whether the animal in danger is trying to appease or intimidate the threat.

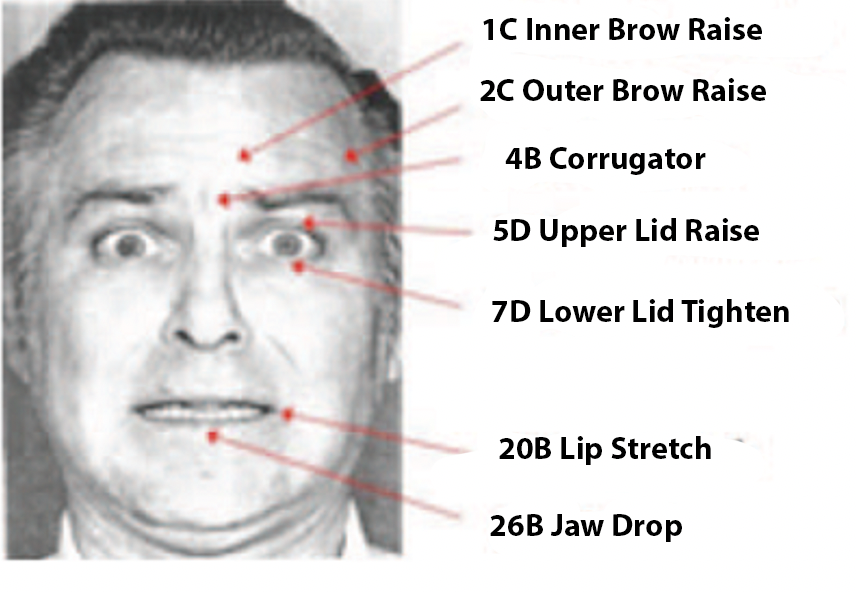

Figure 2 shows the AUs that Ekman and Friesen (1978) found change during a fear experience. Visit this website for a live demonstration of how the AUs for fear change. Evolutionary psychologists have suggested that wide eyes assist the animal is visually exploring the threat. Ekman’s AUs seem to express the appeasement behavior changes. If an animal is aggressing during a fear experience, they might show their teeth more or even more of an anger expression.

Figure 2

Fear AU’s (Ekman & Friesen, 1978)

Long Description

The image is a black and white photograph of a man’s facial expression annotated with labels and lines pointing to various parts of the face. The man’s eyes are wide open, and his mouth is slightly parted, suggesting a surprised or startled expression. The annotations identify specific muscle movements on the face: “1C Inner Brow Raise” and “2C Outer Brow Raise” point to the forehead area; “4B Corrugator” is near the inner brow; “5D Upper Lid Raise” and “7D Lower Lid Tighten” highlight areas around the eyes; “20B Lip Stretch” indicates a position near the corners of the mouth; “26B Jaw Drop” points beneath the chin. These annotations are meant to analyze facial muscular activity related to expressions.

Across several industrialized and isolated cultures, Ekman has found people universally recognize the fear facial expression. In his classic study ( Ekman et al., 1969, review), the majority of participants correctly identified fear, but the Fore and Borneo participants showed lower recognition rates than other countries.

Table 2

Recognition Rates for Fear

| Affect Category | United States | Brazil | Japan | New Guinea (Pidgin responses) | New Guinea (Fore responses) | Borneo* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear (F) | 88 F | 77 F | 71 F | 46 F | 54 F | 40 F |

Reproduced from “Pan-cultural Elements in Facial Displays of Emotion,” by P. Ekman, E.R. Sorenson, and W.V. Friesen, 1969, Science, 164(3875), p. 87, (Pan-Cultural Elements in Facial Displays of Emotion). Copyright Note. For the Fore tribe, some words were in Pidgin language, others in Fore language.

Table 3

Results for Fore Adult Participants (Ekman & Friesen, 1971)

| Emotions shown in the TWO incorrect photographs | # Participants | % Choosing correct face |

|---|---|---|

| Anger, disgust | 92 | 64** |

| Sadness, disgust | 31 | 87** |

| Anger, happiness | 35 | 86** |

| Disgust, happiness | 26 | 85** |

| Surprise, happiness | 65 | 48 |

| Surprise, disgust | 31 | 52 |

| Surprise, sadness | 57 | 28 |

* p < .05., ** p < .01.

Reproduced from “Constants across Cultures in the Face and Emotion,” by P. Ekman, E.R. and W.V. Friesen, 1971, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17(2), p. 127, (Constants across cultures in the face and emotion.). Copyright 2016 by the American Psychological Association

Table 4

Results for Fore Child Participants (Ekman & Friesen, 1971)

| Emotions shown in the ONE incorrect photograph | Numbers | % Choosing correct face |

|---|---|---|

| Sadness | 25 | 92* |

| Anger | 25 | 88* |

| Disgust | 14 | 100* |

(* p) is less than or equal to .01.

Reproduced from “Constants across Cultures in the Face and Emotion,” by P. Ekman, E.R. and W.V. Friesen, 1971, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17(2), p. 127, (Constants across cultures in the face and emotion.). Copyright 2016 by the American Psychological Association

Finally, Ekman and colleagues (1987, for review of study click here ) found that across 10 cultures, the majority of participants identified fear in facial expressions and rated fearful facial expressions as most intensely fear out of 7 possible emotions.

Some other work has found cultural differences in fear facial expressions. In one study (Matsumoto, 1992), participants saw 48 photos of six emotional expressions (anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise). Each emotion was displayed in 8 different photos. Participants viewed all 48 photos one at a time. While viewing each photo, participants picked an emotion label from the following seven emotions: anger, contempt, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. 81.85% of American participants and 54.55% of Japanese participants correctly labeled the fearful expression as fear across the 8 fear photos. Matsumoto (1992) states this provides evidence of universality of fear because the percentages for both groups were beyond chance. Yet, two group differences were found: 1) a significantly greater number of Americans identified fear in the fearful facial expressions and 2) on average, Americans identified 6.5 out of the 8 photos as fear, whereas Japanese identified fewer – about 4.4 photos. In fact, both Japanese and American participants stated the fear photos were the hardest to identify. A similar study by Matsumoto and Ekman (1989) found that 71.12% of Americans correctly identified fear across eight photos, while only 30.82% of Japanese did, forcing the researchers to drop fear from the remainder of their study! In fact, further analyses indicated that 50.35% of the Japanese participants identified the fear photos as surprise.

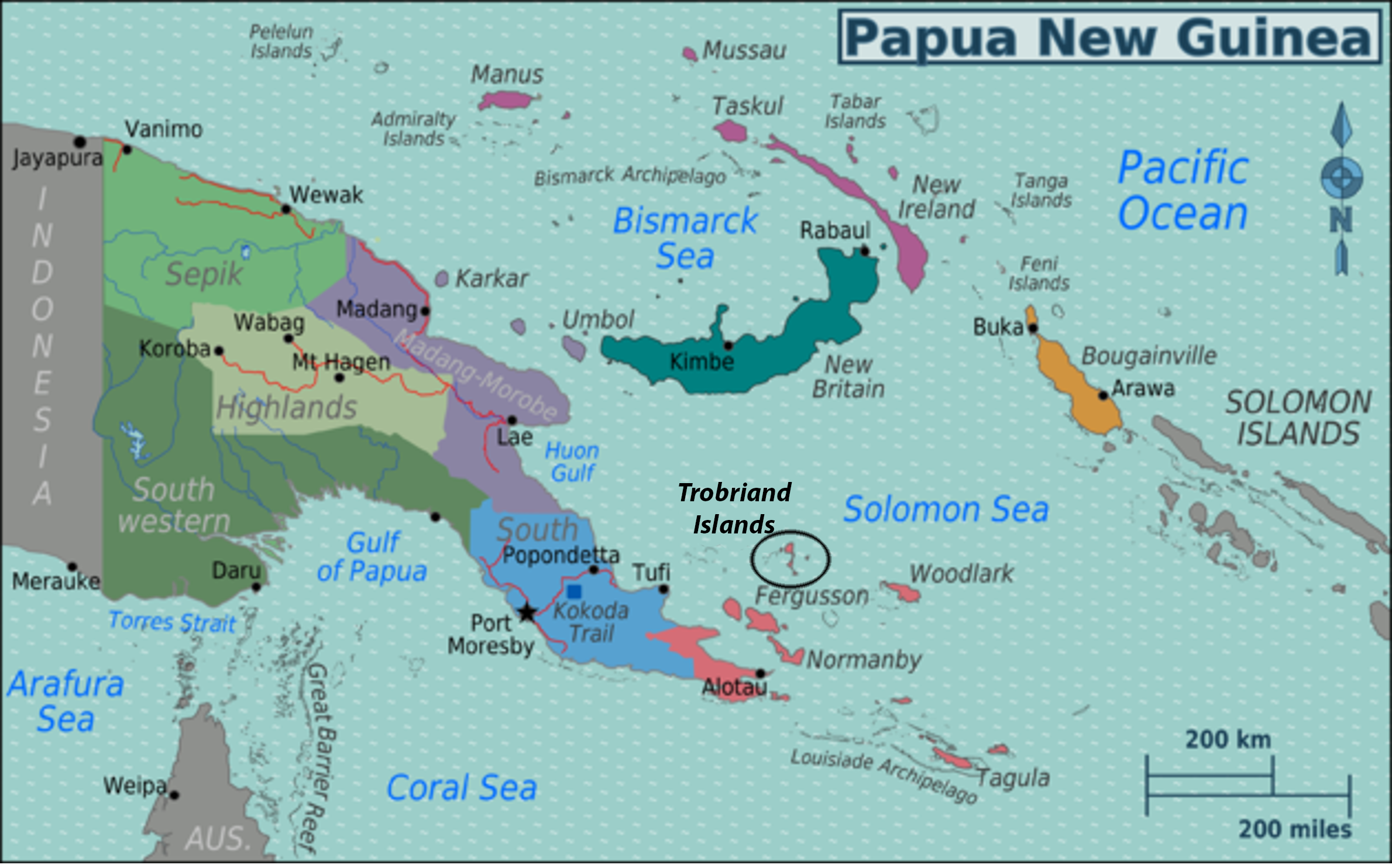

Another study by Crivelli, Russell, and colleagues (2016) compared Spaniards to Trobrianders, an isolated community found in The Trobriand Islands in Papua New Guinea, north of Australia. In both groups, participants were aged 6 to 16 years old.

Long Description

This image is a detailed map of Papua New Guinea and its surrounding regions. It includes:

- Bodies of water: Bismarck Sea, Solomon Sea, Coral Sea, Arafura Sea, and the Pacific Ocean.

- Major islands: New Britain, New Ireland, Bougainville, and the Trobriand Islands with a circle around them.

- Key cities and towns: Port Moresby (the capital), Lae, Madang, Wewak, Vanimo, Rabaul, Kimbe, and Buka.

- Geographic regions: Sepik Highlands and South Western areas are labeled within the country.

- Neighboring areas: Indonesia is shown to the west, and the Solomon Islands to the east.

- A scale bar is included, indicating distances in both kilometers and miles.

The map provides a comprehensive geographic overview of the country, useful for educational, navigational, or cultural reference.

Table 5

List of facial expression changes for 7 facial expression photos

| Correct Emotion Label | Facial Expression Change |

|---|---|

| Happy | Smiling |

| Sad | Pouting |

| Anger | Scowling |

| Fear | Gasping |

| Disgust | Nose Scrunching |

| Neutral | No Change |

Reproduced in table format from “Reading Emotions from Faces in Two Indigenous Societies,” by C. Crivelli, S. Jarillo, J.A. Russell, and J.M Fernández-Dols, 2016, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(7), p. 13 (Reading emotions from faces in two indigenous societies.). Copyright 2020 by the American Psychological Association.

Participants were asked to match emotion words to emotion facial expressions displayed in the photo or video clip. All participants completed their tasks for all five emotions – happy, sadness, anger, fear, and disgust (a within-subjects variable). The facial expressions displayed were the same as in Study 1, in Table 5 above. The photo facial expressions were still photos taken from the video clip. All six facial expressions, including neutral, were shown at the same time for the photos and the video clips. When instructed to select the fear facial expressions, 58% in the static and 47% in the dynamic condition correctly selected the gasping face. (There were no significant differences in the proportion of participants who selected the correct answer in the dynamic or static condition). In general, participants also selected pouting, scowling, and nose scrunching for the fear expression. Finally, Gendron, Barrett and colleagues (2014b) found that both American and Himba participants matched facial expressions with wide eyes into separate piles, indicating that wide eyes may be perceived as fear in both cultures.