Chapter 4: Cognitive Appraisal Theory

Implications Check

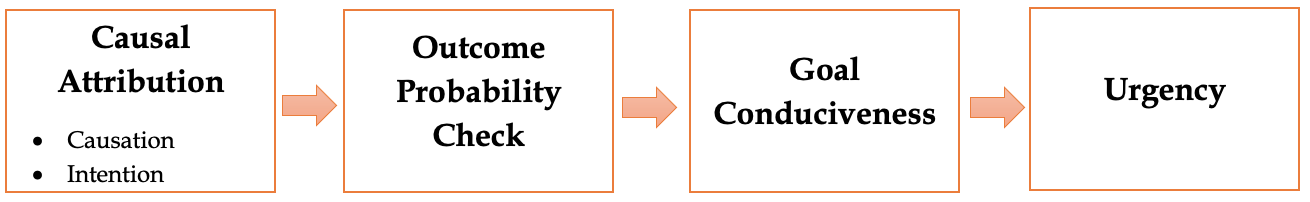

The implications check (see Figure 4) occurs after the goal significance check. During the implications check, the organism determines whether the event hinders or advances survival and basic needs. The implications check includes the following appraisals in order of occurrence: causal attribution, outcome probability check, goal conduciveness, and urgency. Causal attribution occurs when we make causation and intentional attributions. During a causation attribution, we think about whether we make an internal or external attribution for the eliciting event. An internal attribution would mean that we think the event was caused by the self, whereas when an external attribution occurs we conclude the eliciting event was caused by something outside of the self – such as another person, an animal, or an object. Emotions like pride and shame are caused by internal attributions – when we evaluate the self as achieving something good (pride) or doing something harmful (shame). Further, whether we make an internal or external attribution could change the label we provide the emotion. For instance, if we receive a poor grade on the exam and make an internal attribution for this failure (i.e., It’s our fault, we didn’t study enough), then this internal attribution would cause us to feel shame. But, if we fail an exam and make an external attribution (e.g., our teacher is terrible, the exam was too hard), then the external attribution would cause us to label our emotion anger. An intention attribution occurs when we think about whether the internal or external thing caused the event on purpose or by accident. For instance, if we think someone hit our car on purpose that could elicit anger, but if we think they hit our car by accident that might cause a different negative emotion such as sadness or disappointment.

The outcome probability check or possible outcomes check occurs when people assess the likelihood of various outcomes to the event. Scherer (2001) states that how people interpret the probability that the outcomes of an eliciting event would occur could cause a certain emotion. For instance, if we perceive our parents will be very likely to be disappointed by our grade of a B on a statistics exam, then we might experience shame. But, if we perceive our parents will be very likely to be ecstatic about our receiving a B in a difficult statistics course, then we would experience pride or joy!

The goal conduciveness check occurs when we assess whether the outcomes of the eliciting event supports our goals and needs or hinder them. As the outcomes push us closer to achieving our goals or satisfying our needs, the greater goal conduciveness we report. For instance, if we receive a B on a statistics exam, our appraisal might be moderate goal conduciveness, but an A on a statistics exam would cause an even greater appraisal of goal conduciveness. In general, when we perceive that we reached our own goals, we experience pride. As the outcomes push us farther away from achieving our goals or not satisfying our needs, the higher goal obstructiveness we report. Goal conduciveness and goal obstructiveness should be viewed as opposite poles of the same cognitive appraisal dimension. For instance, when someone jumps in front of us in the Starbucks line, we might view that event as preventing us from achieving our goals (a coffee) and from satisfying our needs (thirst!). Typically, an appraisal of high goal obstructiveness (or what we term frustration) causes anger. After goal conduciveness, an urgency check occurs.

Urgency represents the amount of time people perceive they have to achieve their goals or satisfy their needs from the goal conduciveness SEC. As a dimensional cognitive appraisal, high urgency indicates people have little time to achieve their goals/needs, while low urgency suggests an individual has a maximum amount of time to achieve their goals/needs. In fact, Scherer (2001) expands on the urgency definition by combining time and goal significance together, suggesting that high urgency occurs when goals are highly relevant, and people have little time to achieve these goals.

Figure 4

Implications Check SECs