Chapter 10: Disgust

Interpersonal Disgust

Interpersonal disgust and moral disgust make up socio-emotional disgust. Both interpersonal and moral disgust further expand the elicitors from our bodies to other people – hence the term “socio.” Interpersonal disgust is elicited by other people and other people’s body products. Interpersonal disgust is often elicited when we use objects that were used by other people, particularly strangers. Four eliciting events are subsumed under interpersonal disgust:

- Strangeness/Unfamiliarity: aversion to contact with an object used by a stranger

- Misfortune: observing or hearing about a stranger who experienced an accident. This accident does not include an infection or moral transgression.

- Disease: observing or hearing about a stranger diagnosed with a contagious disease

- Moral Taint: observing or hearing about a stranger who committed a moral transgression on purpose.

A study (Rozin et al., 1994b) investigated the disgust elicited by the above four domains. In this study, college students and their parents(!) reported how much they would like to wear a sweater that had been worn by a male stranger with various experiences (see Table 3), AFTER this sweater was washed.

Table 3

Sweater Manipulation and Corresponding Interpersonal Disgust Domain

| Type of Sweater | Description Provided to Participant | Domain of Interpersonal Disgust |

|---|---|---|

| New Sweater | WEaring a brand, new sweater | N/A |

| Healthy Man | Wearing a sweater worn by a healthy, male stranger | Strangeness / Uniqueness |

| Accident | Wearing a sweater worn by a man who lost his leg in a car accident he did not cause | Misfortune |

| Homosexuality | Wearing a sweater worn by a gay man who does not have AIDS | Strangeness or Moral Taint |

| Murder | Wearing a sweater worn by a man who was convicted of murder | Moral Taint |

| AIDS from Transfusion | Wearing a sweater worn by a man who contracted AIDS through a transfusion | Disease |

| AIDS from Homosexuality | Wearing a sweater worn by a gay man who has been diagnosed with AIDS | Disease |

| Tuberculosis | Wearing a sweater worn by a man with tuberculosis | Disease |

Adapted from “Sensitivity to Indirect Contacts with Other Persons: AIDS Aversion as a Composite of Aversion to Strangers, Infection, Moral Taint, And Misfortune,” by P. Rozin, M. Marwith, and C. McCauley, 1994b, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103(3), p. 496. (https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.103.3.495). Copyright 1994 by the American Psychological Association.

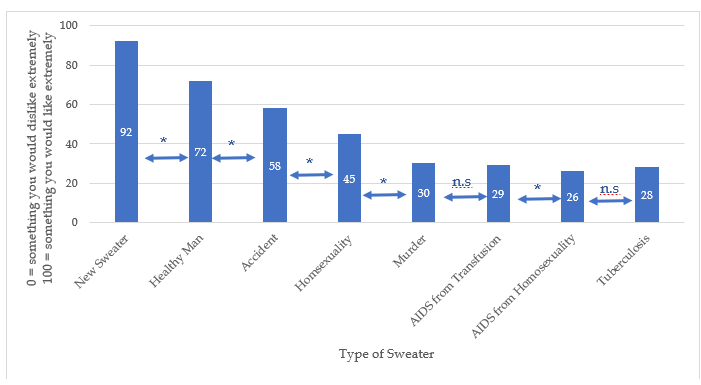

Figure 6

Mean ratings of desire to wear a sweater worn by a male stranger with various experiences

Note. *p<.05 for comparison indicated by arrows. n.s. = not significant

Long Description

The image is a bar graph titled “Type of Sweater,” depicting preferences for different sweater conditions. The y-axis ranges from 0 to 100, where 0 signifies extreme dislike and 100 signifies extreme like. The x-axis lists various sweater types: New Sweater, Healthy Man, Accident, Homosexuality, Murder, AIDS from Transfusion, AIDS from Homosexuality, and Tuberculosis. Each category is represented by a blue bar indicating average preference scores.

- “New Sweater” shows the highest preference with a score of 92.

- “Healthy Man” has a score of 72.

- “Accident” scores 58.

- “Homosexuality” shows a score of 45.

- “Murder” has a score of 30.

- “AIDS from Transfusion” scores 29 with “n.s” below it.

- “AIDS from Homosexuality” scores 26.

- “Tuberculosis” scores 28 with “n.s” below it.

Blue arrows with an asterisk connect some of the bars, indicating statistical significance, except for “n.s” which suggests non-significance.

Adapted from “Sensitivity to Indirect Contacts with Other Persons: AIDS Aversion as a Composite of Aversion to Strangers, Infection, Moral Taint, And Misfortune. ,” by P. Rozin, M. Marwith, and C. McCauley, 1994b, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103(3), p. 498. (https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.103.3.495). Copyright 1994 by the American Psychological Association.