Chapter 13: Positive Emotions

Physiological Changes

SNS/PNS Activation

In two studies by Levenson and colleagues, participants completed the directed facial action task for happiness while physiological measures were taken. In Levenson et al.’s (1990) study on American participants, happy facial expressions caused an increase in heart rate, but this increase was significantly less than the increase for fear, anger, and surprise. For finger temperature, skin conductance, and muscle activity, a happy face caused a small increase from baseline. In a later study (Levenson et al., 1992), American and Minangkabau participants made a happy facial expression. For both groups, making a happy expression resulted in similar small increases in heart rate, finger temperature, and skin conductance. Recall that in this study displaying negative emotions resulted in greater skin conductance for Americans than Minangkabu, but this cross-cultural difference did not occur for the emotion happiness.

Kreibig’s review (2010) investigated ANS changes for seven positive emotions: affection, amusement, contentment, happiness, joy, anticipatory pleasure, pride, and relief. The findings for pride were discussed in the pride chapter and can be found here. Table 21 provides a good summary of the PNS and SNS changes for each emotion. Following this table, the specific findings are discussed.

Table 21

SNS and PNS Changes for Each of the Positive Emotions (Kreibig, 2010)

| Positive Emotion | SNS and PNS Changes |

|---|---|

| Affection | Increased SCR; decreased heart rate |

| Amusement | SNS Activation; PNS Activation |

| Contentment | SNS Withdrawal; PNS Activation |

| Happiness | SNS Activation; PNS Withdrawal |

| Joy | SNS Activation; PNS Activation |

| Anticipatory Pleasure | SNS Activation; PNS Activation |

| Relief | SNS Withdrawal |

| Pride | SNS Activation |

Adapted from “Autonomic nervous system activity in emotion: A review,” by S.D. Kreibig, 2010, ( Biological Psychology, 84(3), p. 406-408) Copyright 2010 Elsevier B.V.

In this study, affection is viewed as similar to love, tenderness, and sympathy. Kriebig found that this emotion construct was linked to decreased heart rate and an increase in skin conductance. This suggests SNS activation, but more work should be conducted. Further, these findings do not consider the presence of several types of love – passionate, companionate, and caregiver.

For amusement, vagal tone and heart rate variability increased. Skin conductance and cardiac PEP also increased. Combined, these suggest activation of both PNS and SNS systems.

Contentment included pleasure, serenity, calmness, peacefulness, and relaxation feelings. Eliciting contentment states caused deactivation of the SNS system (decreased heartrate, respiration, and skin conductance) and activation of the PNS system (vagal tone and heart-rate variability increase).

Happiness caused an increase in heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, and skin conductance suggesting SNS activation. Further vagal tone withdrawal suggests PNS withdrawal.

Joy or elation typically activates both the SNS and PNS systems. Joy causes an increase in heart rate, skin conductance and shortened PEP and an increase in heart-rate variability.

Anticipatory Pleasure includes mostly the feelings associated with sexual arousal but also the feeling of satisfying an appetite. So, anticipatory pleasure is probably the same concept as sensory pleasure. Anticipatory pleasure caused an increase in vagal tone and heart-rate variability and an increase in skin conductance, decreased/increased heart rate. Taken together, these findings suggest both SNS and PNS systems may be activated.

Relief (avoiding a possible shock in the laboratory) caused SNS withdrawal (decrease in skin conductance, decrease in respiration). Another physiological change that occurs is a high frequency of sighing.

The summary of Kreibig’s finding of pride were discussed in the pride chapter. This information is re-pasted below for your convenience.

“Kreibig (2010 ) reviewed five studies that investigated the physiological changes caused by authentic pride. Table X displays the eliciting events and resulting physiological changes for these studies. We cannot draw definitive conclusions because we have so few studies. But, based on these findings we might conclude that pride causes activation of the SNS system, because skin conductance increased. But, the study on experimenter praise (Herrald & Tomaka, 2002) found that cardiac PEP was not shortened, suggesting the SNS system was not activated. The only indicator we have on PNS is a study that elicited pride with film clips and found that heart-rate variability did not change, suggesting the PNS is not activated (Gruber et al., 2008)” (Yarwood, 2021, Pride Chapter).

Overall, Kreibig’s (2010) findings show that SNS and PNS activity vary with the specific positive emotion. Remember, that constructivist and dimensional theorists view positive emotions as simply positive valence and any level of arousal. So, it could be that positive feelings simply vary in arousal or activation and that we try to categorize these feelings with specific labels.

Shiota et al. (2011) elicited five positive emotions in the lab and then measured physiological changes. These five emotions were anticipatory enthusiasm, attachment love, nurturant love, amusement, and awe (see Table 22). View anticipatory attachment as the emotion joy.

Table 22

Description of 5 Positive Emotions and Elicitation Method in Laboratory

| Positive Emotion | Elicited by | Elicitor Used in Lab |

|---|---|---|

| Anticipatory Enthusiasm | Anticipation of Rewards | Slides with dollar amount; dollar amount increased with each slide |

| Attachment Love | Attachment Figure | Childhood characters such as Big Bird and Papa Smurf |

| Nurturant Love | Caring for young | Baby Animals |

| Amusement | Physical / Cognitive play; humor | Far Side Cartoons |

| Awe | New large events that do not fit with current schemas | Panoramic Views |

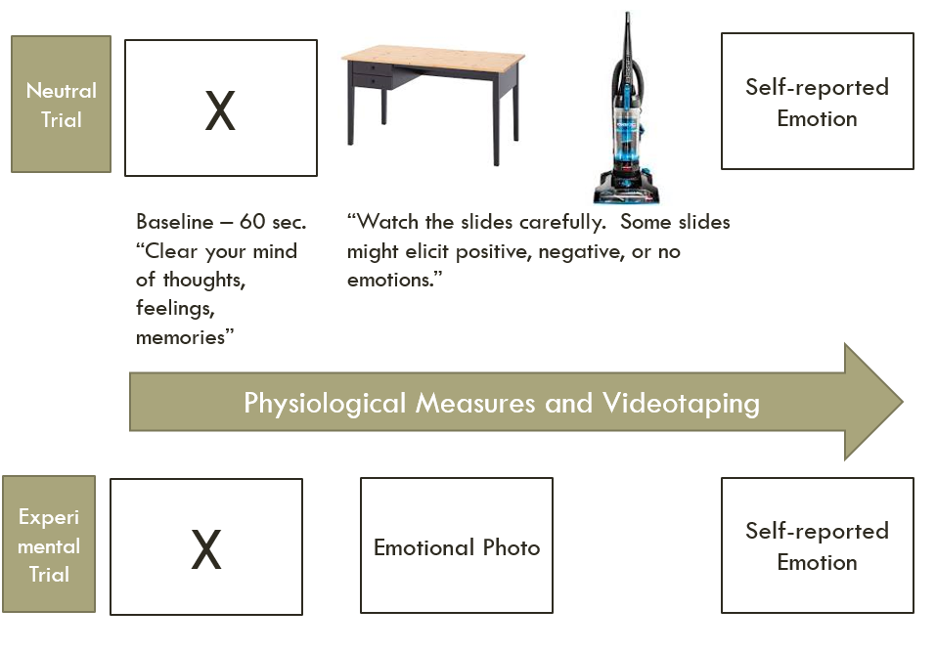

Participants completed a baseline and experimental trial for each emotion. In experimental trials, a neutral emotion or one of the five positive emotions was elicited (displayed in Figure 14). During all trials, physiological measures were taken, and participants were videotaped. To acquire baseline measures, participants were shown an X for 60 seconds and told to clear their mind – while baseline measures were taken. Then, in the neutral trial, participants were shown slides of neutral household objects – while baseline measures were taken. In the emotion trials, participants were shown slides of the corresponding elicitors. At the end of the trial, participants self-reported their subjective feelings using 10 emotions: amusement, anger, awe, contentment, disgust, enthusiasm, excitement, fear, love/attachment, sadness, and tenderness/compassion.

Figure 14

Pictorial Display of Procedures from Shiota et al. (2011)

Long Description

A diagram outlining a psychological experiment involving neutral and experimental trials. The diagram is divided into two main sections: the top row representing the “Neutral Trial” and the bottom row representing the “Experimental Trial.”

In the “Neutral Trial” section, there is a box labeled “Neutral Trial” on the left, followed by a large “X” in the next box, indicating an undefined or neutral element. Next to it are two images: one of a desk and chair, and another of a vacuum cleaner, representing neutral stimuli. Below, it says to “Watch the slides carefully. Some slides might elicit positive, negative, or no emotions.”

The “Experimental Trial” section at the bottom mirrors the arrangement of the top. It has a box labeled “Experimental Trial,” followed by another large “X,” and a box labeled “Emotional Photo,” suggesting the introduction of an emotional stimulus. A text box to the side is labeled “Self-reported Emotion.”

Across the center of the diagram is an olive-colored arrow with the text “Physiological Measures and Videotaping,” indicating that these measures occur parallel to both trials.

In the next few paragraphs, I will explain the findings for each of the psychological measures. For a good overview of the findings for each positive emotion, please skip down to Table 23.

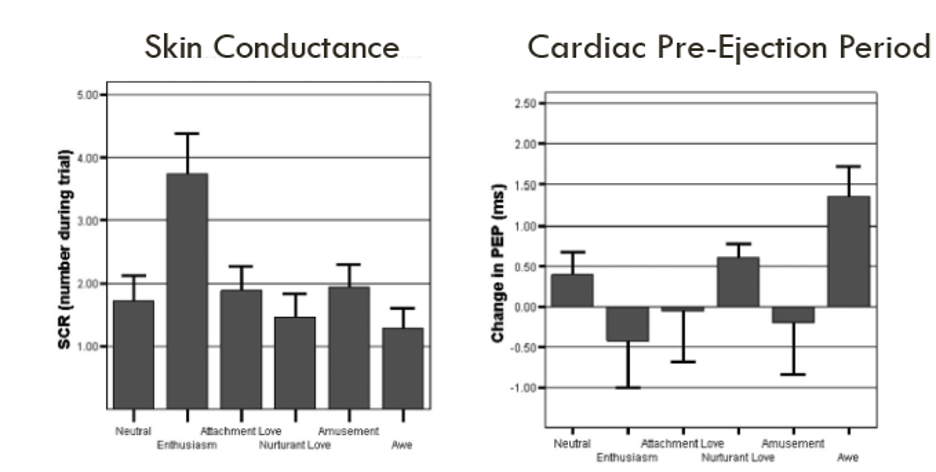

Figure 15 shows the changes in SNS activity for measures that provide pure measures of SNS activity. For skin conductance (SCR), anticipatory enthusiasm showed the greatest increase from baseline compared to the other emotions. Amusement’s increase from baseline was greater than awe but not greater than neutral condition.

For cardiac PEP, remember that lengthening of PEP indicates withdrawal of SNS while shortening of PEP indicates SNS activation (for a review, go here). Awe resulted in a lengthening of PEP and this lengthening was significantly greater than the five other emotion states. Nurturant love showed lengthening of PEP that was shorter than awe, but did not differ from other conditions.

Figure 15

Results for Pure Measures of SNS Activity

Long Description

The image shows two bar graphs side by side. The left graph is titled “Skin Conductance” and displays the SCR (number during trial) on the vertical axis, ranging from 0 to 5. The horizontal axis lists emotional states: Neutral, Enthusiasm, Attachment Love, Nurturant Love, Amusement, and Awe. Enthusiasm has the highest bar, followed by Amusement and Attachment Love, with Neutral and Awe having lower values.

The right graph, titled “Cardiac Pre-Ejection Period,” measures Change in PEP (ms) on the vertical axis, ranging from -1.50 to 2.50. The same emotional states are listed on the horizontal axis. The bars show Enthusiasm and Awe with positive values, while Attachment Love and Amusement have negative changes. Nurturant Love is around zero.

Reproduced from “Feeling good: Autonomic nervous system responding in five positive emotions” by M.N. Shiota, S.L. Neufeld, W.H. Yeung, S.E. Moser, and E.F. Perea, 2011, Emotion, 11(6), p. 1375 (https://doi.org/ 10.1037/a0024278) Copyright 2011 American Psychological Association.

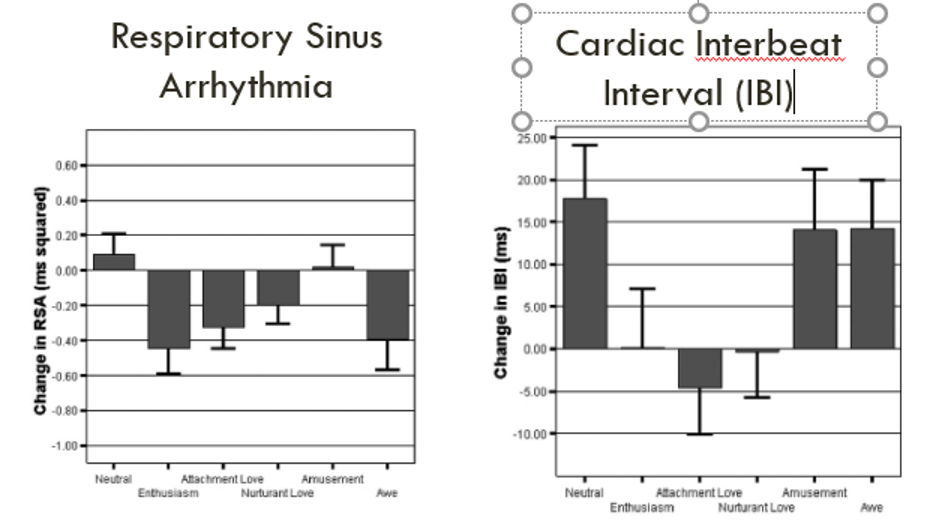

Figure 16 shows the changes from baseline for RSA and cardiac interbeat interval (IBI). RSA is a pure measure of PNS activity. In general, all emotion states caused a decrease in RSA from baseline except for the neutral and amusement conditions which showed zero change from baseline. Overall, these findings suggest that for positive emotions the PNS system was not activated. Except for neutral and amusement condition, all other emotion states demonstrated a decrease in RSA, which indicates the PNS system was not activated. Enthusiasm showed a decrease in RSA from baseline and this decrease was significantly different from amusement and neutral condition. Awe, Attachment Love, and nurturant love each caused a decrease in RSA that was significantly different from the neutral condition, but not different from the four other positive emotion states.

Cardiac Interbeat Interval (IBI) is not a pure measure of PNS activity. IBI is inversely correlated with SNS and IBI has a positive relationship with PNS influence. For attachment love, IBI decreased from baseline and this decrease was significantly greater than the neutral, amusement, and awe conditions. Nurturant love also decreased significantly from baseline and this decrease was greater than the neutral condition. Taken together, these findings suggest that attachment and nurturant love caused withdrawal of PNS and activation of SNS. Amusement and awe showed an increase in IBI from baseline and this increase was greater than attachment love, but was not different from the neutral condition. These findings suggest that the neutral, amusement, and awe conditions might have caused an increase in PNS activation and SNS withdrawal.

Figure 16

RSA and IBI Activity

Long Description

The image contains two bar graphs side by side. The left graph is titled “Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia” with the y-axis labeled as “Change in RSA (ms squared)” ranging from -1.00 to 0.60. It displays six bars representing different emotional states: Neutral, Enthusiasm, Attachment Love, Nurturant Love, Amusement, and Awe. Some bars extend below the zero line, indicating negative changes, while others are above the line. The right graph is titled “Cardiac Interbeat Interval (IBI)” with the y-axis labeled as “Change in IBI (ms)” ranging from -10.00 to 25.00. It also displays six bars for the same emotional states, with varying heights and directions. Both graphs include error bars.

Reproduced from “Feeling good: Autonomic nervous system responding in five positive emotions” by M.N. Shiota, S.L. Neufeld, W.H. Yeung, S.E. Moser, and E.F. Perea, 2011, Emotion, 11(6), p. 1375 (https://doi.org/ 10.1037/a0024278) Copyright 2011 American Psychological Association

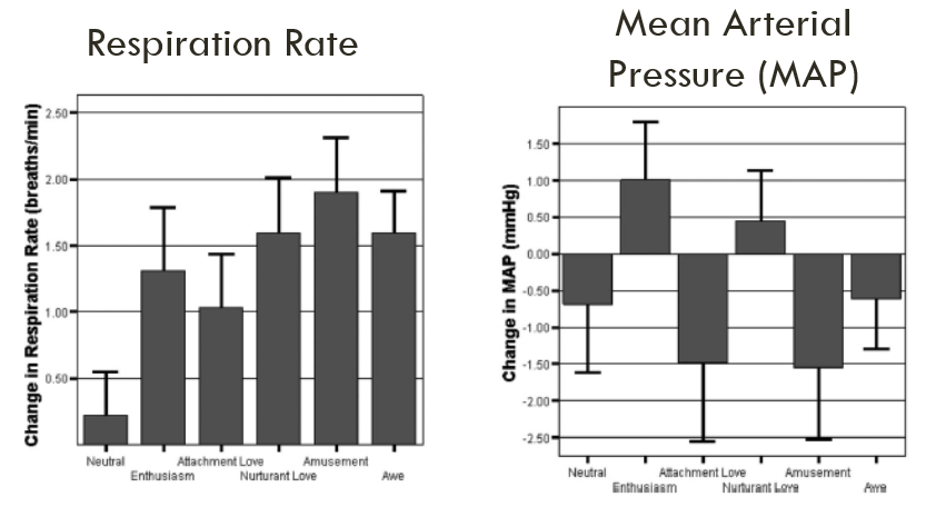

Figure 17

Respiration Rate and MAP

Long Description

The image consists of two vertically aligned bar graphs, each depicting different physiological measures. The left graph shows “Change in Respiration Rate (breaths/min)” across six emotional states: Neutral, Enthusiasm, Attachment Love, Nurturant Love, Amusement, and Awe. The bars vary in height, with “Amusement” showing the highest increase. The right graph displays “Change in Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) (mmHg)” with the same emotional conditions. Bars also vary, with “Neutral” resulting in the largest decrease. Both graphs include error bars indicating variability.

Reproduced from “Feeling good: Autonomic nervous system responding in five positive emotions” by M.N. Shiota, S.L. Neufeld, W.H. Yeung, S.E. Moser, and E.F. Perea, 2011, Emotion, 11(6), p. 1375 (https://doi.org/ 10.1037/a0024278) Copyright 2011 American Psychological Association.

Table 23 provides a good summary of how the PNS and SNS systems changed for each emotion. Keep in mind that this is one study and that more research is needed to confirm these changes. As you review the below table, think about possible limitations to this study (Hint: think about the ways in which the researchers elicited each emotion in the laboratory).

Table 23

Summary of SNS and PNS Findings for Each Positive Emotion

| Positive Emotion | Elicited by | Elicitor used in Lab | SNS | PNS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticipatory Enthusiasm | Anticipation of rewards | Slides with dollar amount; dollar amount increased with each slide | SNS Activation

Increase in SCR; Shortening PEP |

PNS Withdrawal

Decrease in RSA |

| Attachment Love | Attachment Figure | Childhood characters such as Big Bird and Pap Smurf | SNS Activation

Decrease in IBI; No change in MAP or PEP |

PSN Withdrawal

Decrease in RSA, and Decrease in IBI |

| Nurturant Love | Caring for Young | Baby Animals | SNS Activation

Decrease in IBI; Increase in Resp. Rate, No change in for MAP |

PNS Withdrawal

Decrease in RSA, and Decrease in IBI |

| Amusement | Physical / Cognitive Play; Humor | Far Side Cartoons | Not Clear

Increased Resp. Rate and Increase IBI suggests SNS withdrawal activation |

Not Clear

Increase in IBI suggests PNS Activation |

| Awe | New large events that do not fit with current schemas | Panoramic Views | SNS Withdrawal

Lengthening PEP; Increase in IBI; Decrease in RSA |

PNS Withdrawal, Decrease in RSA, OR PNS activation, Increase in IBI |

Adapted from “Feeling good: Autonomic nervous system responding in five positive emotions” by M.N. Shiota, S.L. Neufeld, W.H. Yeung, S.E. Moser, and E.F. Perea, 2011, Emotion, 11(6), p. 1371, 1373-1376 (https://doi.org/ 10.1037/a0024278) Copyright 2011 American Psychological Association.