Chapter 3: Basic Emotion Theory and Social Constructivist Theory

Subjective Feelings

Lastly, we want to explore whether changes in subjective feelings are universal or culturally different. In general, studies have identified cross-cultural differences in the experiences of mixed emotions (typically measured as the experience of happiness and sadness at the same time). Typically, studies will compare the following three groups of participants: 1) people born in and living in Eastern cultures 2) people born in an Eastern culture and living in a Western culture and 3) people born in and living in a Western culture. In general, people born in and living in Eastern cultures tend to exhibit a positive correlation between negative and positive emotions, indicating they experience mixed emotions (Perunovic, Heller, & Rafaeli, 2007; Schimmack et al., 2002; Shiota, Campos, Gonzaga, Keltner, & Peng, 2010). People born in and living in a Western culture exhibit a negative correlation between positive and negative emotions, suggesting they experience either positive OR negative emotions. Finally, individuals born in East Asia but living in Western cultures show a pattern similar to Western individuals, but the negative correlation between positive and negative emotions is weaker (in comparison to Western individuals). So, in general we could conclude that East Asians experience mixed emotions, Westerners experience either positive or negative emotions, while individuals born in Asia but living in a Western culture fall in between these two groups. In conclusion, Western linear cultures think of positive and negative emotions as negatively correlated. This means Westerners believe negative and positive emotions cannot occur together. In contrast, dialectical cultures such as those found in East Asia perceive negative emotions and positive emotions to be positively correlated with each other. This may be because East Asian participants consider the entire context when identifying emotions in others and are more aware of positive and negative aspects of the situation. Thus, East Asian participants tend to report that they are experiencing both positive and negative emotions. In fact, work has found that experiencing negative emotions is not strongly tied to well-being for collectivist cultures (Kuppens et al., 2008). It may be that collectivist cultures are more comfortable experiencing and accepting negative emotions and thus view these negative emotions as separate to their own sense of happiness. One reason for this cultural difference may be that Americans may be less comfortable feeling mixed emotions, so they quickly resolved the mixed emotion episode by moving toward a more negative or more positive feeling. Or as mentioned earlier, Americans’ interpretations of the emotion episode might only focus on the positive OR negative part of the context and not both aspects simultaneously.

Beyond cultural differences in self-reported mixed emotions, some evidence shows that people in different cultures experience different types of emotions. Socially disengaged emotions (sometimes called ego-focused emotions) are elicited by events directly related to the self (e.g., pride and anger). Conversely, socially engaged emotions (sometimes called other-focused emotions) are elicited by events related to others or to our relationships with other people (e.g., shame, love, vicarious pride, and embarrassment).

To test cultural differences in these emotions, Kitayama, Mesquita, and Karasawa (2006) recruited Japanese and American participants. At the end of each day for 14 days, participants recalled the “most emotional episode of the day” (Kitayama et al., 2004, p. 893). Then, each day, participants reported how strongly they experienced 27 different emotions during that emotional episode (Table 13 shows examples of these emotions). These 27 emotions were categorized into categories based on whether they are positive/negative and disengaging/engaging.

Table 13

Emotion Categories

| Emotion Type | Emotion |

|---|---|

| Positive Engaging | Friendly Feelings

Respect Sympathy |

| Positive Disengaging | Proud

Superior Self-esteem |

| Negative Engaging | Guilt

Indebted Ashamed Afraid of cuasing trouble on another |

| Negative Disengaging | Sulky feelings

Frustration Angry |

Adapted from “Cultural Affordances and Emotional Experience: Socially Engaging and Disengaging Emotions in Japan and the United States,” By. S. Kitayama, B. Mesquite, and M. Karasawa, 2006, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), p. 893. (Cultural affordances and emotional experience: Socially engaging and disengaging emotions in Japan and the United States.). Copyright 2006 by the American Psychological Association.

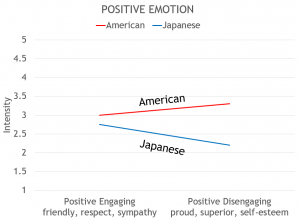

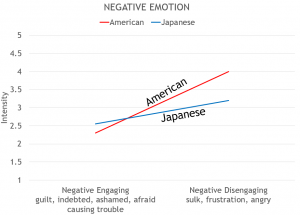

Figure 18

Differences in Americans’ and Japanese self-reported positive engaging and positive disengaging emotions (left) and negative engaging and disengaging emotions (right) over a 14 day period.

Long Description

The image is a line graph titled “POSITIVE EMOTION” that compares the intensity of positive emotions between American and Japanese individuals. The graph includes:

X-axis: Two emotion categories:

Positive Engaging (e.g., friendly, respect, sympathy)

Positive Disengaging (e.g., proud, superior, self-esteem)

Y-axis: Emotion intensity, on a scale from 1 to 5

Lines:

Red line: Represents American participants

Blue line: Represents Japanese participants

Trends Observed:

Americans show a slight increase in intensity from engaging to disengaging emotions (from ~3 to above 3.5).

Japanese individuals show a decrease in intensity from engaging to disengaging emotions (from ~2.75 to below 2.5).

This suggests cultural differences in how positive emotions are experienced or valued, with Americans reporting stronger disengaging emotions and Japanese individuals reporting stronger engaging emotions.

Long Description

The image is a line graph titled “NEGATIVE EMOTION” that compares the intensity of negative emotions between American and Japanese individuals. The graph includes:

X-axis: Two emotion categories:

Negative Engaging (e.g., guilt, indebtedness, shame, fear of causing trouble)

Negative Disengaging (e.g., sulking, frustration, anger)

Y-axis: Emotion intensity, on a scale from 1 to 5

Lines:

Red line: Represents American participants

Blue line: Represents Japanese participants

Trends Observed:

Americans show a clear increase in intensity from engaging to disengaging emotions (from ~2.5 to ~3.5).

Japanese individuals show a slight increase (from ~2.6 to just above 2.8), with less variation between the two emotion types.

This suggests that Americans may experience or report disengaging negative emotions (like anger or frustration) more intensely than engaging ones, while Japanese individuals show a more balanced emotional intensity across both types.

Adapted from “Cultural Affordances and Emotional Experience: Socially Engaging and Disengaging Emotions in Japan and the United States,” By. S. Kitayama, B. Mesquite, and M. Karasawa, 2006, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), p. 894. (Cultural affordances and emotional experience: Socially engaging and disengaging emotions in Japan and the United States.). Copyright 2006 by the American Psychological Association.

Let’s look at the left figure in Figure 18 . American participants experienced positive disengaging emotions more intensely than positive engaging emotions. Japanese participants reported the opposite – they experienced positive engaging emotions more intensely than they did positive disengaging emotions. When comparing the two cultures, Americans reported higher intensity for positive disengaging emotions than Japanese, but there were not cultural differences for the positive engaging category.

Now, let’s look at the right figure in Figure 18. Both Americans and Japanese reported experiencing negative disengaging emotions more strongly than negative engaging emotions. But, the difference in intensity between disengaging and engaging emotions was stronger for Americans. Comparing cultures, Americans reported greater intensity for disengaging emotions than Japanese, but again cultural differences did not exist for engaging emotions.

These findings suggest that across a two-week period, American participants (vs. Japanese participants) reported greater intensity for emotions tied directly to the self, a clear cross-cultural finding! But, American and Japanese participants did not report differences in intensity for engaging emotions – a universal finding! Comparing emotions within a culture does provide more evidence for cross-cultural differences – such that Americans experienced their disengaging emotions more intensely, whereas those from Japan experience their engaging emotions more intensely. Of course, one limitation is the emotion friendliness. Friendliness seems to be more representative of another construct – a personality trait!

Another way subjective feelings can be categorized is as powerful emotions or powerless emotions. Powerful emotions are emotions that display one’s own status and power. Powerless emotions are those emotions that occur when we blame the self and report low perceived ability to cope. A study (Fischer, Mosquera, & van Vianen, 2004) investigated how gender and culture influenced participants’ subjective feelings. Men and women from 37 different countries were recruited. Some participants were from cultures with a high GEM (Gender Empowerment Measure, a construct used to measure gender equality in a given country), whereas other participants were from low GEM cultures. Countries were assigned a high GEM score if the country had equal division of the sexes and if women were heavily involved in positions of power, such as politics, economics, and the workplace. Low GEM countries were those in which men held more power than women. Participants were instructed to recall a time they felt six different emotions, and then to rate the emotion along two dependent variables: 1) self-reported intensity of emotion and 2) presence/absence of anger or crying facial expressions. The two powerful emotions, typical of the male gender role, were anger and disgust. The powerless emotions, typical of the female gender role, were fear, sadness, shame, and guilt.

First, cultural and gender differences were not found for the intensity of powerful emotions (e.g., anger, disgust). The main finding from this study was that women’s self-reported intensity for powerless emotions was not significantly different in low and high GEM cultures. This means that as a country becomes more gender-equal (moves from low to high GEM), women do NOT adopt the male role of low levels of intense powerless emotions. Men living in low GEM countries did report more intense powerless emotions than men living in high GEM countries. This means that as a culture becomes more gender-equal (moves from low to high GEM), men in turn adopt the typical male role of less intense powerless emotions. In other words, men in high GEM countries report less intense fear, sadness, shame and guilt. This finding could be interpreted another way – such that as a culture becomes less gender-equal (moves from high to low GEM) men report more intense powerless emotions. Why? This probably doesn’t have to do with gender roles at all! It might be that men in low GEM countries experience many obstacles that could cause powerless emotions, such as war, conflict, and corruption. One final result to look at is the incidences of the anger facial expression. In low GEM countries, women self-reported fewer anger expressions than men. But in high GEM countries, men and women self-reported similar experiences of the anger facial expression. Together, these findings show that as a culture becomes more gender-equal (moves from low to high GEM), women adopt the masculine role by expressing powerful emotions, but men do not adopt the feminine role. Actually, the results showed that in countries with gender inequality men also adopt the feminine role of powerless emotions.