Chapter 14 – Emotion Regulation

Suppressing and Reappraising Positive Emotions

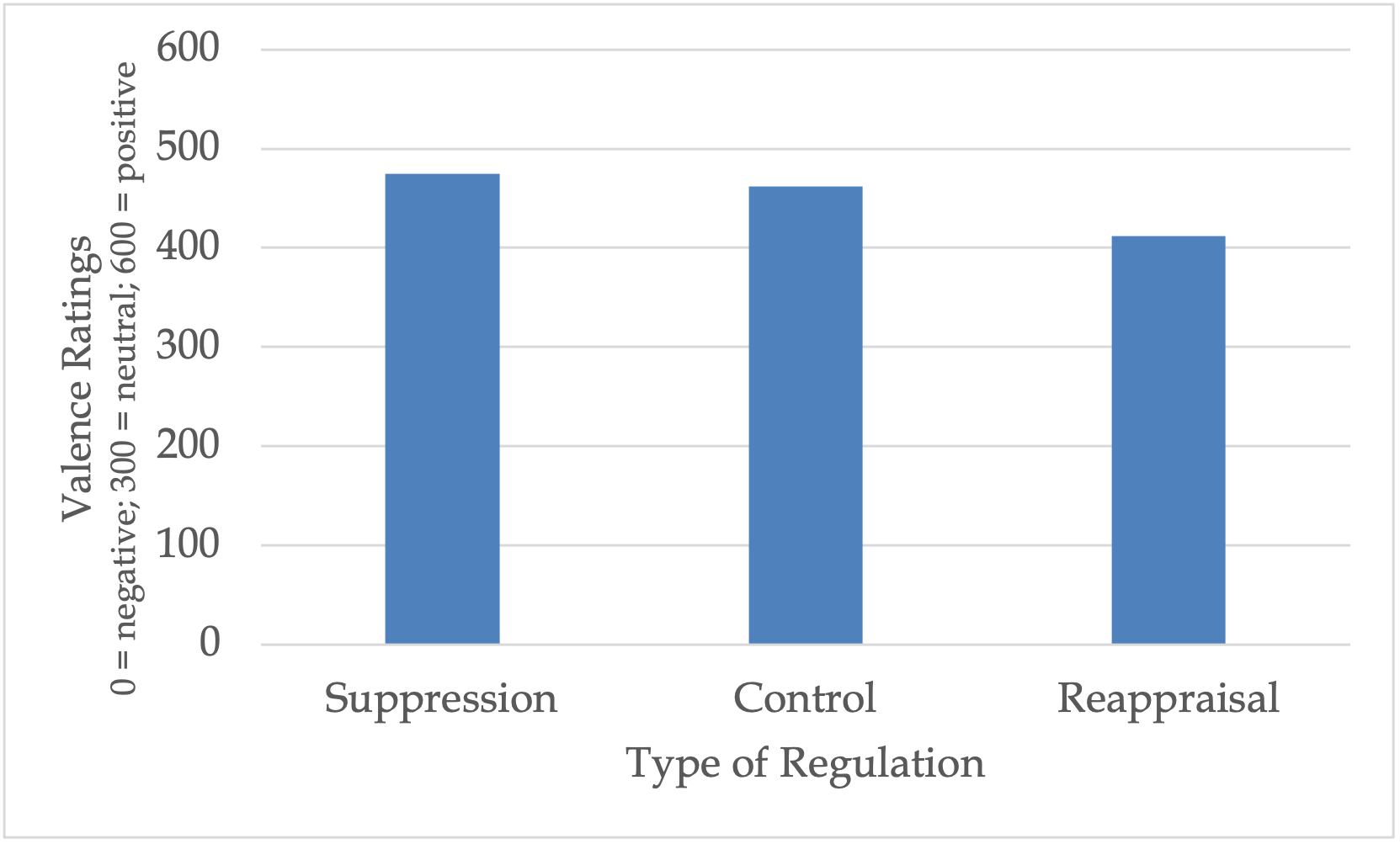

Impact of Type of Regulation on Self-Reported Valence

Long Description

A vertical bar chart depicting valence ratings based on the type of regulation. The chart includes three vertical blue bars representing different categories: Suppression, Control, and Reappraisal. The y-axis is labeled “Valence Ratings” with values ranging from 0 to 600, where 0 is negative, 300 is neutral, and 600 is positive. The x-axis is labeled “Type of Regulation.” All bars are of similar height, indicating similar levels of valence across the categories, with values slightly above 400 for each.

Adapted from “Mindful Regulation of Positive Emotions: A Comparison with Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression” by F. Lalot, S. Delplanque, and D. Sander, 2014, Frontiers in Psychology, 5(243), p. 5 (https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00243). Copyrighted 2014 by the Authors and Open Access.

Figure 15

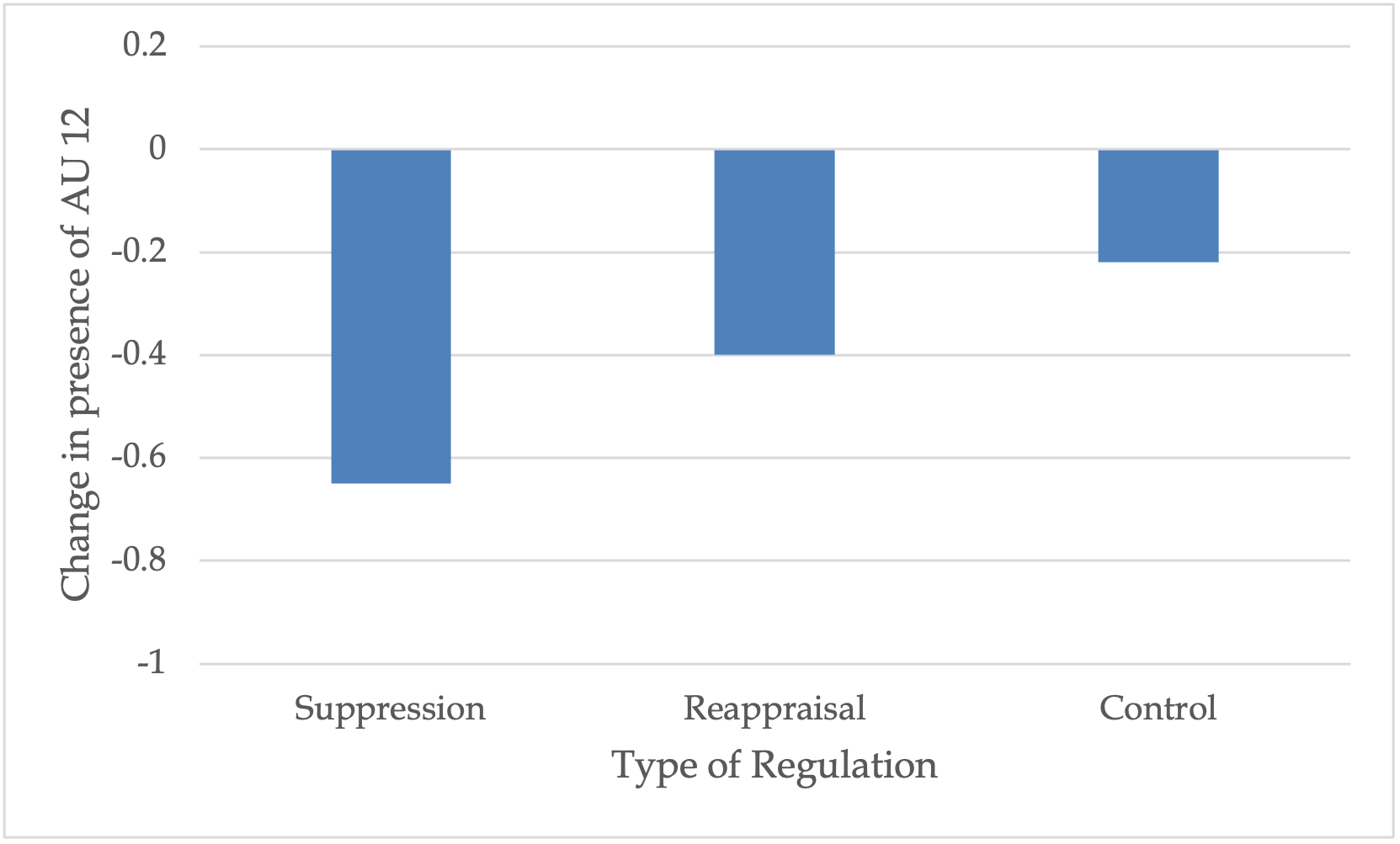

Influence of Regulation Strategy on Presence of AU12 Lip Corner Puller

Long Description

A vertical bar chart displaying the change in presence of AU 12 across three different types of regulation: Suppression, Reappraisal, and Control. The Y-axis represents the change in presence ranging from -1 to 0.2, while the X-axis lists the types of regulation. Each bar is colored blue. The Suppression bar shows a change of approximately -0.7, the Reappraisal bar shows a change of around -0.3, and the Control bar indicates a change of about -0.2.

Adapted from “Mindful Regulation of Positive Emotions: A Comparison with Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression” by F. Lalot, S. Delplanque, and D. Sander, 2014, Frontiers in Psychology, 5(243), p. 6 (https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00243). Copyrighted 2014 by the Authors and Open Access.

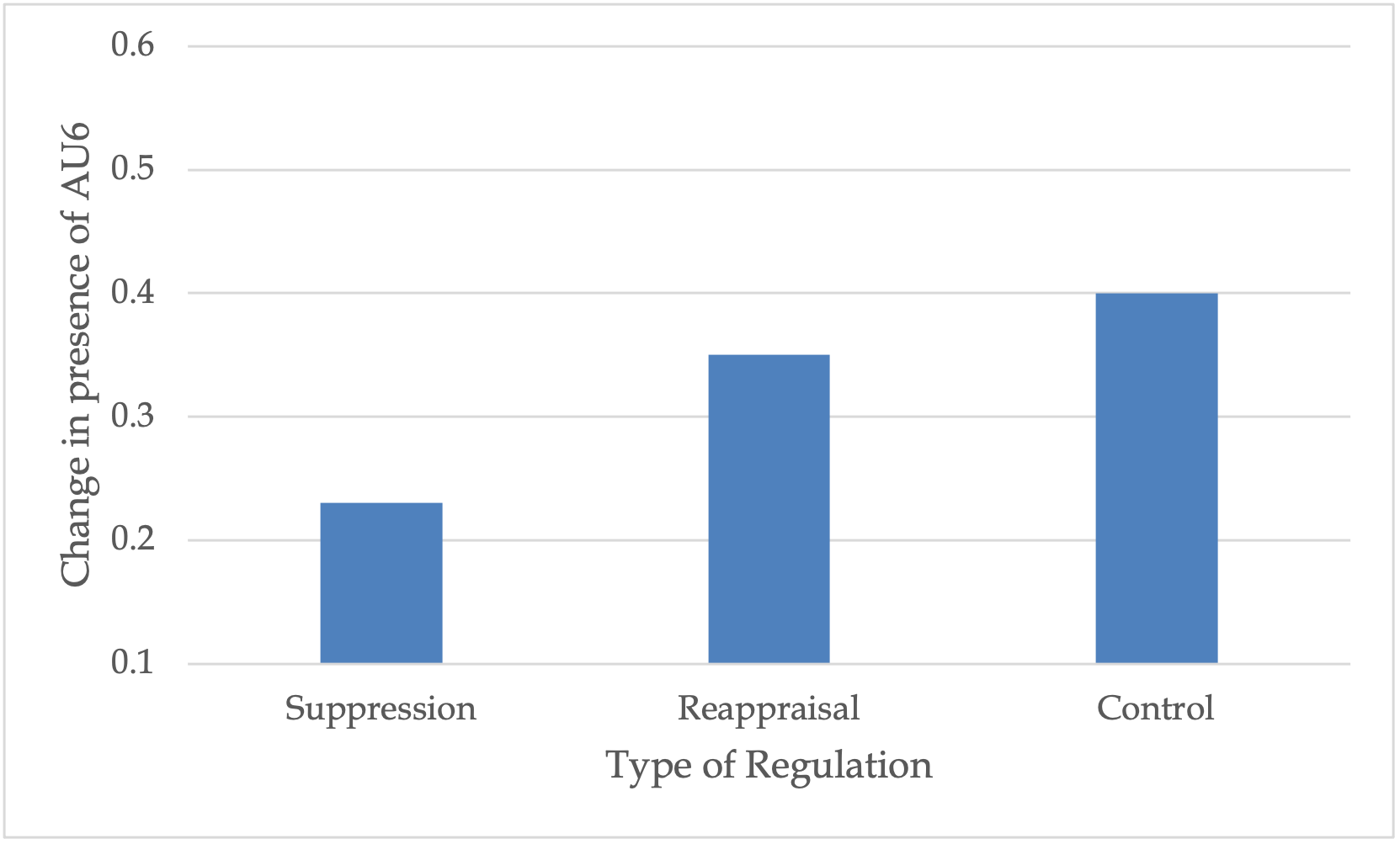

Figure 16

Influence of Regulation Strategy on Presence of AU6 Cheek Raiser

Long Description

A vertical bar graph displays the change in presence of AU6 across three types of regulation: Suppression, Reappraisal, and Control. The x-axis represents the “Type of Regulation,” while the y-axis indicates the “Change in presence of AU6” ranging from 0.1 to 0.6. Three blue bars represent each type of regulation. The bar for Suppression is the shortest, indicating a change slightly above 0.2. The Reappraisal bar is taller, showing a change just above 0.3. The Control bar is the tallest, with a change of 0.4.

Adapted from “Mindful Regulation of Positive Emotions: A Comparison with Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression” by F. Lalot, S. Delplanque, and D. Sander, 2014, Frontiers in Psychology, 5(243), p. 6 (https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00243). Copyrighted 2014 by the Authors and Open Access.

Most of the work on increasing positive emotions focuses on reappraising negative emotion experiences in a neutral or positive light. But some studies have started investigating other ways of increasing positive emotions, such as amplifying arousal or positive valence. Helping people to up-regulate positive emotions might be one intervention for certain psychological diagnoses. For a review of using the process model of emotion to increase positive emotions, please read this review article by Quoidbach et al (2015).

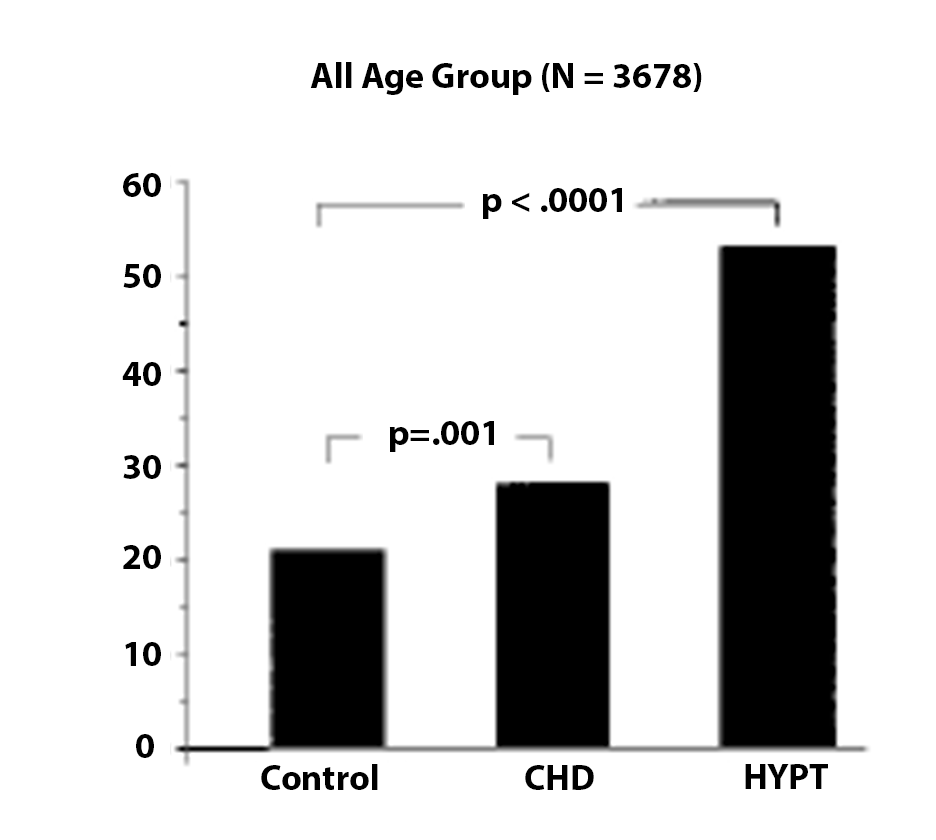

Suppression may be a strategy that individuals diagnosed with depression use more frequently. Some initial work by Gross and colleagues (Ehring et al., 2010) has found that during a sad film clip, recovered-depressed individuals self-reported that they spontaneously suppressed more during a sad film clip compared to control participants. There was not a difference in reappraisal between the two groups. This indicates that in a sad situation, depressed individuals might automatically fall back on suppression as a strategy to down-regulate their negative emotions. But, when asked instructed to suppress or reappraise during another sad film clip, recovered-depressed and control participants did not show differences in their self-reported emotions after regulating. In fact, both groups reported fewer negative emotions when reappraising versus suppressing. This finding tells us that suppression doesn’t result in more negative emotions for depressed individuals. Another study (Flynn et al., 2010) found that expressive suppression was associated with depression for men, but not for women (this means gender moderates the relationship between suppression and depression). This is interesting because men tend to suppress more than women, but women report more depression and negative affect than men. So, for men, suppression is a good predictor of a depression diagnosis. Interestingly, the Type D (“distressed”) personality trait describes an individual who has a tendency to chronically suppress their negative emotions. One study (Denollet, 2005) found that approximately 55% of hypertension (HYT) and 28% of congestive heart disease (CHF) patients were high on Type D, significantly higher than the 22% of the control participants with the Type D personality trait (see Figure 17). In another study (Schiffer et al., 2005), participants diagnosed with CHF were recruited. Compared to CHF patients low on Type D, CHF high on Type D exhibited poorer health, and more symptoms of depression. In fact, Type D was a better predictor of health status beyond age, gender, severity of CHF, and cause of CHF.

Figure 17

Percentage of Participant Groups who Score High on Type D

CHD, Type D (%): 28

HYPT, Type D(%): 54

Long Description

A vertical bar chart comparing three groups: Control, CHD, and HYPT among a sample size of 3678 participants, labeled as “All Age Group (N = 3678)” at the top. The y-axis represents an unspecified measurement scale ranging from 0 to 60. Three black bars represent each group, showing differing values. The Control group has a bar reaching slightly above 20, the CHD group has a bar slightly below 30, and the HYPT group has a bar close to 60. Two significance markers indicate statistical differences: p = .001 between Control and CHD, and p < .0001 between CHD and HYPT.

Reproduced from “DS14: Standard Assessment of Negative Affectivity, Social Inhibition, and Type D Personality” by J. Denollet, Psychosomatic Medicine, 67(1), p. 93 (https:/doi.org/ 10.1097/01.psy.0000149256.81953.49). Copyright 2005 by the American Psychosomatic Society.

Amplification

The research on amplification is not as extensive as the work on suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Whether amplifying our negative emotions has a good or bad outcome depends on 1) the valence of the emotion 2) how much of the emotion we are amplifying and 3) the situation in which we are amplifying. Recall that some work by June Gruber and colleagues (Gruber et al., 2011) suggests that increasing our positive emotions is only good up to a point. Too much positive emotion could be detrimental because we are not aware of negative eliciting events in our surroundings, because the positive emotions are not appropriate for the situation, or because too much positive emotion might be symptomatic of mania and other disorders. (link back to this webpage here). Similarly, amplifying negative emotion might work when preparing for a soccer game, but people who continuously amplifying their anger experience physical health issues such as cardiovascular disease.

Watch the video “How a Chair Revealed the Type A Video” to learn how cardiologist Friedman and Rosenman discovered the Type A trait from their waiting room chairs.