Chapter 3: Basic Emotion Theory and Social Constructivist Theory

Vocal Affect: Social Constructivist Perspective

Gendron, Roberson, van der Vyver, and Barrett (2014a) conducted a similar study, but changed the methodology to address limitations with Sauter et al. (2010). (Note: Lisa Barrett, a social constructivist, was an author on this study). Participants were recruited from the Himba tribe and from Boston. Participants listened to vocal sounds from male and female native English speakers, then verbally provided one word or phrase to identify the emotion. Thus, in this study, participants were not provided two choices from which to select. Below are the vocal sounds that represented each emotion.

Table 11

Vocal Sounds and Corresponding Emotion from Gendron et al. (2014a)

| Discrete Emotion Portrayed | Vocalization |

|---|---|

| Amusement | Giggle, Laughter |

| Anger | Guttural yell, Growl |

| Disgust | “Ewww” |

| Fear | Scream |

| Relief | Sigh |

| Sadness | Cry |

| Sensory Pleasure | “Mm mmm” |

| Surprise | “Ahhh-ahhh” |

| Triumph | “Woohoo” |

Reproduced from “Cultural Relativity In Perceiving Emotion From Vocalizations,” by M. Gendron, D. Roberson, J.M. van der Vyver, and L.F. Barrett, 2014a, Psychological Science, 25(4), p. 912, (Cultural Relativity in Perceiving Emotion From Vocalizations). Copyright 2014 The Authors.

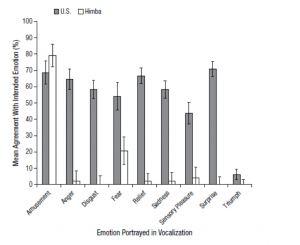

Two coders determined whether the participants’ emotion label matched the expected emotion conveyed in the vocal sound. The dependent variable was measured as the mean percentage of all trials the Himba and Boston participants got correct. In 69% of the trials and 79% of the trials, the Himba and Boston participants, respectively, labeled laughter as amusement. But, on the remaining emotions, the Himba participants correctly labeled a small number of vocal sounds. Interestingly, further results showed that the Himba and Boston participants correctly identified the valence of most vocal sounds — valence meaning whether the sound represented a positive, negative, or neutral state — although Boston participants were more likely to correctly identify the valence of the sound. Finally, both groups of participants were able to identify the arousal level of most sounds – whether the emotion was high or low in arousal, or a more neutral state. Again, Boston participants were more likely to identify the correct arousal level, particularly because Himba participants often mislabeled low arousal emotions like sadness. Generally, these findings suggest vocal changes for discrete emotions are not universal, but that general changes in arousal or valence may be universal.

Here is an audio clip describing her study.

Figure 14

Mean Percent Of Responses in which Intended Emotion Selected for Corresponding Vocalization

Long Description

Emotion Portrayed in Vocalization

This bar chart compares the mean agreement percentage between U.S. and Himba participants regarding the intended emotion portrayed in vocalizations. The vertical axis represents the mean agreement with the intended emotion (in percent), ranging from 0% to 100%. The horizontal axis lists ten emotions: Amusement, Anger, Disgust, Fear, Relief, Sadness, Sensory Pleasure, Surprise, and Triumph.

Two bars represent each emotion:

Dark gray bars represent U.S. participants

White bars represent Himba participants

Error bars are included to show variability.

Key observations:

U.S. participants consistently show higher agreement percentages than Himba participants across all emotions.

Highest agreement among U.S. participants occurs with Surprise, Relief, and Amusement.

Himba participants show relatively high agreement with Amusement but low agreement with Anger, Relief, Sadness, Surprise, and Triumph.

The greatest discrepancy between groups is observed in Anger and Relief.

Reproduced from “Cultural Relativity In Perceiving Emotion From Vocalizations,” by M. Gendron, D. Roberson, J.M. van der Vyver, and L.F. Barrett, 2014a, Psychological Science, 25(4), p. 914, (Cultural Relativity in Perceiving Emotion From Vocalizations). Copyright 2014 The Authors.